UC mountaineer, galactic explorer

Graduate Kevin Wagner discovered a planet with three suns, expanding our understanding for how new planets form.

In your face, Amerigo Vespucci.

September 2018

September 2018

Boldly Bearcat

Finding his voice

Danger in the tap

Virtual defense

Global game changer

Celebrating UC's Bicentennial

Past Issues

Past IssuesBrowse our archive of UC Magazine past issues.

Graduate Kevin Wagner discovered a planet with three suns, expanding our understanding for how new planets form.

In your face, Amerigo Vespucci.

By Michael Miller

513-556-6757

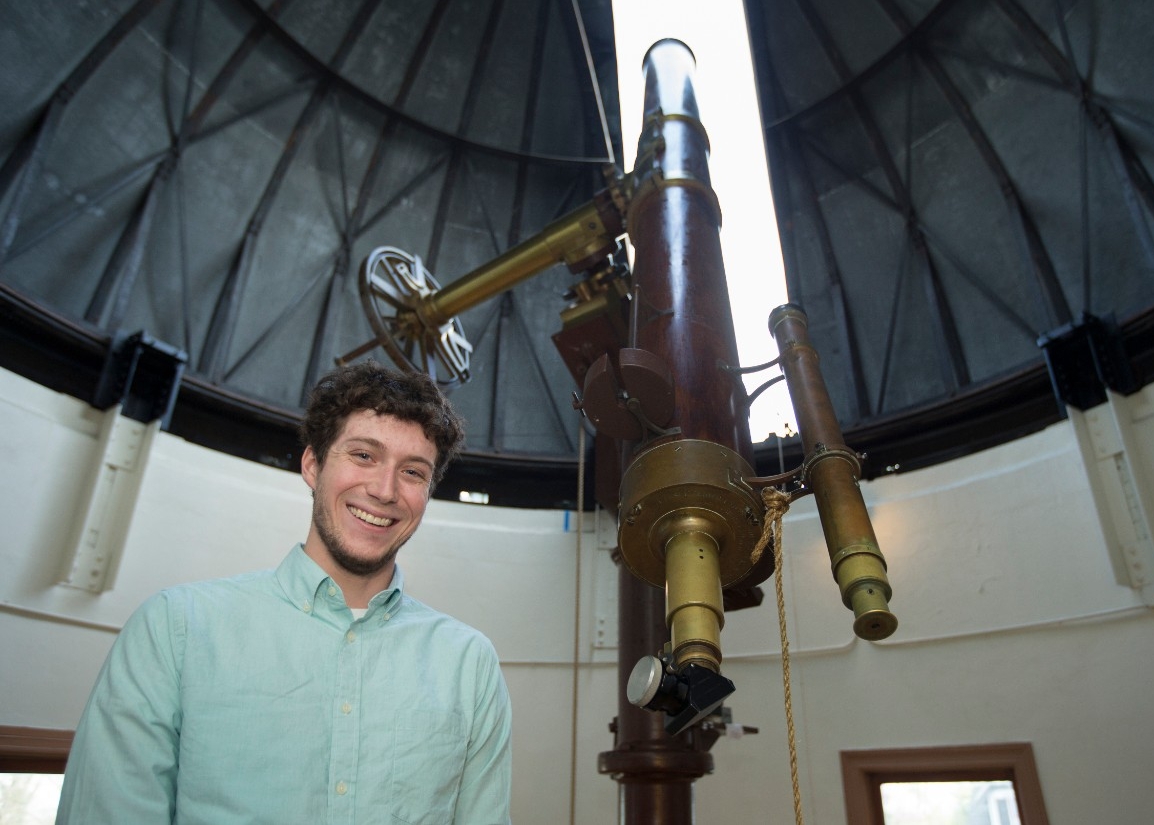

Photos by Lisa Ventre/UC Creative Services

April 12, 2017

University of Cincinnati graduate Kevin Wagner is an explorer in the truest sense of the word.

As a climber trained in the UC Mountaineering Club, Wagner scaled the precipitous El Capitan in California’s Yosemite National Park. And as an astrophysicist, he accomplished what few explorers have ever done: He captured images of a new planet he discovered.

Wagner, 23, a graduate student at the University of Arizona, was the lead author for an international team last year that identified and captured images of HD 131399Ab, a planet named for its solar system.

The revelation fired the imaginations of stargazers with his description of the planet’s never-setting suns and strange orbit. The discovery is expected to help astronomers refine theories about how new planets are formed.

Wagner, a graduate of the McMicken College of Arts and Sciences and a native of Northern Kentucky, returned UC in April to give a talk on his findings to some of his former physics classmates and professors. This time instead of asking the questions, he was answering them.

“We really haven’t had an opportunity to study a world like this before,” Wagner said.

The European Southern Observatory commissioned an artist's rendering of Scorpion-1b, a planet with three suns that UC astrophysics graduate Kevin Wagner discovered and imaged. (Photo: ESO/L. Calçada/M. Kornmesser)

Wagner has always been interested in the night sky. But it was only as a student at Newport Catholic High School that Wagner realized he could turn that curiosity into a career.

“At the time I was watching Carl Sagan’s ‘Cosmos’ series and realized that astronomer and astrophysicist were actual jobs one could have,” he said. “I applied for the astrophysics program at UC and never thought about doing anything else.”

Wagner now calls the planet “Scorpion-1b” after the Scorpius-Centaurus association of stars his team examined in their planetary survey from the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile.

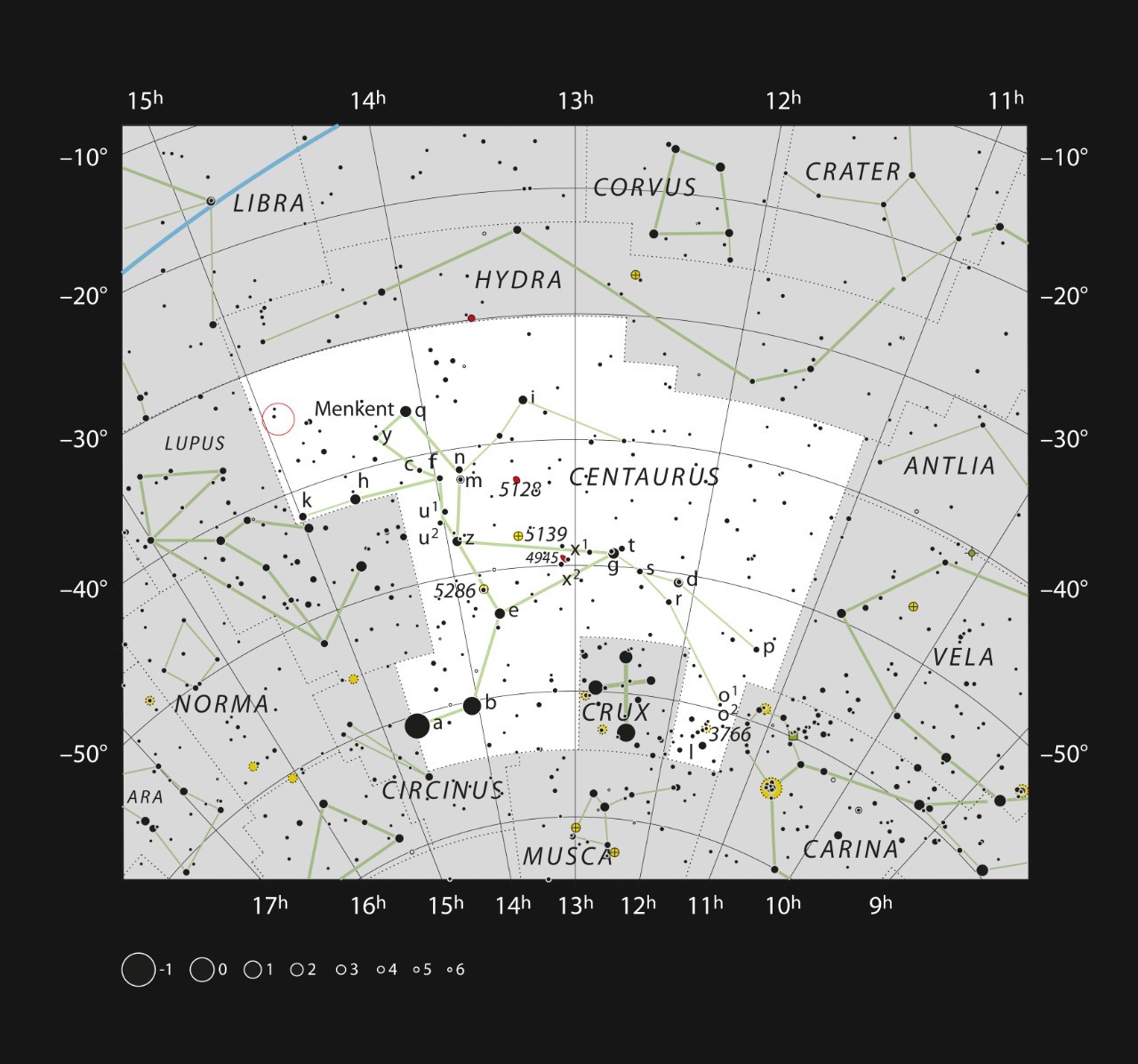

Scorpion-1b is situated near the Southern Cross, a constellation as familiar to Australians and South Americans as the Big Dipper is to the northern hemisphere.

The planet is 1,300 times bigger than Earth. If you took a walk there, you wouldn’t need a coat. It’s a balmy 1,070 degrees Fahrenheit. But of course you can’t walk on Scorpion-1b because it’s composed entirely of gas.

The planet is bathed in constant light from its three suns for one-third of its solar year — or about 140 Earth years. For much of that time, the planet has a traditional sunrise and sunset, albeit repeated three times per day.

But what Wagner and other astrophysicists find most interesting is the planet’s exotic orbit, circling the largest sun as two other suns circle them.

“We’re interested in following the planet in its orbit to learn if it is stable or unstable. Right now we can only say that it’s very close to that line. Another year or two of observations should give us a definitive answer,” he said.

The red planet of Scorpion-1b circles one sun while two other stars orbit around them in this artist's interpretation by the European Southern Observatory. (ESO/L. Calçada/M. Kornmesser)

Astronomers discover new planets all the time. NASA has a tally of more than 2,300, some identified by citizen scientists who pore over reams of raw data the agency provides.

But Scorpion-1b is one of just a handful of planets outside our solar system to be photographed. More accurately, Wagner and his team used SPHERE (or the Spectro-Polarimetric High-Contrast Exoplanet Research instrument) to peer through the Earth’s atmospheric distortions and the distant sun’s blinding light to render an image of the planet.

Astronomers identify new planets in one of three ways, according to astronomer and UC physics professor Michael Sitko.

Next year NASA will launch the James Webb Space Telescope, which has cameras and spectrometers that can record extremely faint signals.

“Technology has made all the difference, especially when you talk about exoplanets,” Sitko said of planets beyond our solar system.

“Finding a planet is one of the rarest and most-sought-after accomplishments, but it’s actually becoming slightly more common with dedicated telescopes looking for transiting planets,” Wagner said. “However, it’s very uncommon to actually image a planet, which is how we discovered Scorpion-1b.”

Wagner said Sitko gave him his first opportunity to conduct research at UC that propelled his career.

“He’s a world expert in planet formation,” Wagner said. “Dr. Sitko allowed me to start doing research as a first-year undergraduate, which put me well ahead of the curve.”

Wagner’s team is looking at the planet in different wavelengths to learn more about its atmosphere. Since astrophysicists can see direct light from the planet — at least, for the part of the year when the Earth’s sun isn’t in the way — they can study its atmosphere in a way that is impossible with other distant planets, he said.

Wagner’s discovery became international news, reported in hundreds of media outlets as diverse as Nature, National Geographic, CNN and the New York Times.

“We expected the discovery to generate some attention, but we had no idea how widely it would be picked up by the international media,” Wagner said.

The planet’s multiple suns prompted comparisons to the iconic twin sunsets of Tatooine depicted in “Star Wars.”

Discoveries such as Scorpion-1b raise tantalizing questions, some of which skew to the existential.

“One of the goals of astronomy is to search for origins. What is our place in the universe?” Sitko said. “Not knowing all the answers doesn’t bother me. The universe is a big place.”

These questions have broad appeal not just for physicists.

Wagner has devoted his adult life to exploration, not just in the astrophysical sense. At UC, he was an instructor at the recreation center’s climbing wall. Twice, he launched a climbing expedition up the daunting El Capitan. The first effort ended when his team ran out of water midway up the granite face.

But Wagner summitted on his second attempt, a five-day climb in which they slept on platforms suspended thousands of feet above the valley. He considers it his biggest accomplishment next to discovering a new planet.

“Many of my closest friends emerged from my climbing experiences through UC,” he said.

Wagner returned to Chile this year to resume his intermittent long-distance relationship with his new world. He and other researchers were able to collect a full night of data and, perhaps more importantly, take more images that he will publish in his next research paper.

“I think this really captured people’s imaginations by showing us that something as familiar as a sunset might be totally different on an alien planet,” he said.

Kevin Wagner was a member of the UC Mountaineering Club and worked at the climbing wall at the university's recreation center. After graduating from UC, he climbed El Capitan in Yosemite National Park. (Photos by Jordan Stone and Hal Stone.)

Scorpion-1b is found in Centaurus as viewed from Earth's southern skies. The planet's three stars are found 320 light years from Earth near the Southern Cross. (ESO/Digitized Sky Survey 2/N. Risinger (skysurvey.org). Music: Johan B. Monell)

As a student at UC, Kevin Wagner volunteered at the Cincinnati Observatory, which still has its original telescope from 1845.

It’s huge: four times bigger than Jupiter, the largest planet in our solar system, or about 1,300 times bigger than Earth.

It’s hot: The atmosphere is 1,070 degrees Fahrenheit.

It’s young: It formed just 16 million years ago compared to Earth, which is approximately 4.5 billion years old.

It’s far: about 28 billion miles away from the closest of its three suns. Our sun is just 93 million miles away.

How long is a day there?

Is its orbit stable or unstable?

Are there other planets, or possibly Earth-like planets, orbiting closer to the stars?

The three stars that light Scorpion-1b (the red dots) are found in Centaurus near Crux or the Southern Cross. (ESO/IAU and Sky & Telescope)

Do you have an adventurous spirit? At UC, astrophysics students use the latest techniques to explore the universe. Apply to the Department of Physics or explore other programs on the undergraduate or graduate level.