Down the Drive

Natalia Trotter, JD '19, found community and purpose in UC's Urban Morgan Insitution for Human Rights in the College of Law. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II

ACADEMIC EXCELLENCE

Global Social Justice

In its 40th year, UC’s Urban Morgan Institute for Human Rights has become a world leader in international human rights law education and scholarship

Although born in Mexico City and raised in Guadalajara, Natalia Trotter felt as if she straddled two worlds as a dual citizen of the U.S. and Mexico. Trotter, the daughter of Christian missionaries who regularly visited family each year in the U.S., often found herself torn between two very different cultures and identities, with a foothold in each.

It wasn’t until she arrived at the University of Cincinnati College of Law that the 2019 UC graduate finally found a community where she felt her two worlds converge. Here, in UC’s Urban Morgan Institute for Human Rights, Trotter found an ethnically diverse group of students and faculty who share her passion for both human rights activism and international law.

“I have friends from Venezuela and Mexico and all different parts [of the world] who have come to UC through the Urban Morgan program,” says Trotter. “I’ve been able to connect with that community here, but also with people from the U.S. who have an international perspective and a desire to see human rights prosper.”

It’s that shared passion for global social justice that’s united the 1,500 students who’ve learned the ins and outs of international human rights law at the institute since its launch 40 years ago. Hailed as the first of its kind in the nation when it was founded in 1979, the Urban Morgan Institute resulted from a relationship between attorney William Butler and his longtime client Urban Morgan, a former Cincinnatian and son of the founder of the U.S. Playing Card Co.

When Morgan died, he made Butler sole trustee of his fortune, with the stipulation that the money be spent at UC as the attorney saw fit. Butler was a distinguished human rights activist who had successfully argued such landmark civil rights cases as Engel v. Vitale, the 1962 “school prayer case,” before the U.S. Supreme Court and negotiated one-on-one with the Shah of Iran on measures needed to eliminate torture and repression. He recruited Bert Lockwood to create the Urban Morgan Institute for Human Rights within the UC College of Law.

The institute, which holds the distinction of being the oldest endowed human rights institute in the nation, offers students the opportunity to meet with leading figures in the international community, join the Human Rights Quarterly, the world’s leading academic journal on the subject and travel across the globe each summer on “externships.”

“It affords incoming students the opportunity to begin their work with the institute in their first year,” says Lockwood. And, he adds, “It is not unusual for students during their presentations about their summer externships to express the belief that these were life changing.”

The opportunity to travel abroad and work with a human rights organization was nothing short of an “incredible experience,” says Trotter. Her first summer experience saw her working in the Dominican Republic with International Justice Mission, an organization dedicated to ending sex trafficking, where she researched ways the U.S. could bring to justice Americans who commit sex tourism crimes abroad.

The following summer, Trotter traveled to Los Angeles, where she spent 10 weeks working on the case of an asylum-seeker with mental disabilities who, with Trotter’s help, later won her bid to remain in the U.S. Trotter also spent a week earlier this year volunteering with the Southeast Immigrant Freedom Initiative at an immigration detention center in Folkston, Georgia. The project, organized by the Southern Poverty Law Center, enlists and trains volunteer lawyers to provide free legal representation to detained immigrants facing deportation proceedings in the Southeast.

“Not a lot of law students get that opportunity to go and work internationally and see different countries and legal systems,” says Trotter. “I’ve had some amazing opportunities at UC working with vulnerable populations.”

After graduating in May, Trotter quickly lined up a job at the Texas-based Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services, which provides free and low-cost legal services to underserved immigrant children, families and refugees. While interviewing for the position, she discovered that her interviewer, a managing attorney at the organization, is also a UC graduate who participated in the Urban Morgan Institute.

“I really wanted to go into law to give people who don’t have a voice that opportunity to be heard and understood and represented,” says Trotter. “It’s really cool to see how Urban Morgan is at the center of a lot of people who have gone out to do incredible work.”

— R. Richardson

The Urban Morgan Institute for Human Rights will celebrate its 40th anniversary with a weekend of festivities. Here’s a lineup of events planned:

- Friday, Oct. 25: Welcome reception, Fairfield Inn & Suites

- Saturday, Oct. 26: Conference at UC College of Law; cocktails and dinner at The Phoenix, downtown Cincinnati

- Sunday, Oct. 27: Conference at UC College of Law

Claudio Rebola's class works with older adults in the community to make more realistic and advanced robotic pets. Photo/Andrew Higley

INNOVATION AGENDA

High-tech pets

UC team improves upon an existing line of robotic cats and dogs to provide care and companionship

It’s no secret that pets bring joy to their owners’ lives — studies show they can even increase people’s life spans.

For some older populations, having a pet isn’t possible. Perhaps they can’t care for an animal or their retirement community doesn’t allow it. Robotic companions have entered the market to fill that void, and one UC associate professor is reimagining these high-tech pets to not only provide companionship, but care.

Claudia Rebola is the associate dean for research in UC’s College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning. Together with graduate students from DAAP and UC’s College of Engineering and Applied Science, Rebola set out to design innovative new features and functionality for an existing line of robotic pets that could expand capabilities, like checking a user’s vital signs, and improving the dog’s realism.

In 2017, while working at Rhode Island School of Design, Rebola collaborated in acquiring federal funding for a robotic pet project with researchers from Brown University and Butler Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island, and industry partner Hasbro, one of the largest toymakers in the world. The team received a $1 million National Science Foundation grant to reenvision the existing line of Joy For All Companion Pets (now owned by Ageless Innovation) through the addition of artificial intelligence.

Rebola’s team is reimagining the pets from appearance to function, collaborating to create the next-generation robotic intelligence that provides psychosocial support for older adults.

Feedback from focus group sessions with older adults in the community led the class to add enhanced realistic features to the robot dog, from its fur to movements. They modeled the new prototype after the Yorkshire terrier — one of the most popular breeds among older adults, they discovered.

Other students centered on caregiving support possibilities. The result is four areas of care: detecting/preventing falls, connecting users to caregivers and loved ones, checking vital signs and providing helpful reminders. The class envisions a smart collar for the robotic pets that can enable these functions.

“I’m very proud of my students for working on this for months when it typically takes years to work on robotics,” Rebola says.

— J. Kern

Ella shows off her purple prosthetic hand created by UC students. Photo/Paul Grundy

REAL WORLD

Play ball

Using a UUC-created prosthetic, five year old throws out first pitch for the Cincinnati Reds at Great American Ball Park

Ella Morton took the mound with the confidence of a Cy Young winner pitching a no-hitter.

Standing next to mascot Rosie Red, the 5-year-old right-hander wound up and hurled the ball toward the plate and then waved to the cheering crowd with her purple left hand.

Ella was one of the first beneficiaries of a prosthetic made by University of Cincinnati students in the nonprofit group EnableUC. Combining engineering and medicine, the club manufactures 3D-printed parts to create inexpensive custom prosthetics.

A birth defect stunted Ella’s left hand. But by bending her wrist, she can close the fingers of her prosthetic to pick up, grip and hold things — like a major league baseball in front of a stadium of enthusiastic Bearcats.

The new purple hand looks like a real one down to the fingernails that Ella can paint.

“We wanted to make one that looked more like a human hand than a robot,” says Jackson Romelli, a biomedical engineering student who serves as president of EnableUC.

The UC club provides free prosthetics to other children like Ella. Unlike artificial appendages that can cost thousands of dollars, EnableUC’s parts are inexpensive and easy to replace so children can play as hard as they want without worrying about breaking them. Ella has been through several iterations since her first two years ago.

Now the group is working on a similar project for a child in Trinidad.

“There aren’t many times when you can have such a profound impact on someone’s life. When we see how much joy our work brings, it’s indescribable,” Romelli says.

And with the confident way she handled the pitcher’s mound at Great American Ball Park, Ella clearly has big things ahead of her.

“All of these children are go-getters. They’re fearless,” Romelli says.

— M. Miller

Students from UC’s colleges of medicine, nursing and pharmacy are working together to provide care for the uninsured. Photo/Colleen Kelley

URBAN HEALTH

Care for all

UC students and physicians offer free services to uninsured at local health clinic

Medical students and several UC doctors opened a free health clinic in northern Hamilton County this summer with the aim of increasing access to health care services for uninsured Tristate residents.

Caroline Hensley, a UC master’s of public health student working at the Crossroads Health Center in 2016, noticed several of the Spanish-speaking patients lacked health insurance. Many of them lived outside of the central city core and had unreliable transportation to access a clinic.

So once Hensley entered the UC College of Medicine, she began working with other students who shared a passion to develop a free student-run health clinic.

They reviewed previous proposals, conducted a needs assessment, researched how student-run health clinics operated in other parts of the country, involved students and faculty in the UC colleges of pharmacy and nursing and approached clinical faculty for assistance.

The group found the population most likely to benefit from a clinic was based in northern Hamilton County and reached out to the Healing Center, an established ministry of the Vineyard Cincinnati Church, for a potential site. “The Healing Center has so many amazing existing resources,” says Hensley, who is now entering her last year of medical school at UC. “What’s most impressive is they provide such dignity for their clients, and that was evident from the first time we visited. It is a beautiful place that strives to care for clients holistically. It is a wonderful organization.”

Hensley says the Healing Center also offers a variety of social services for people needing assistance. The UC clinic leases its space for $1 annually from the center and has received donated medical equipment for exam rooms. Students have also raised $34,000 in donations to aid the clinic’s operations.

“There is a great need in Cincinnati for a clinic of this nature,” says Shawn Krishnan, a second-year UC medical student. “When clients come into the clinic they will be triaged at the front desk, and individuals in need of immediate care will go over to the exam room and interact with a patient navigator.”

“By starting the clinic we are helping to ease some of the health disparities seen by Hamilton County residents.”

—Keely Morris, fourth-year pharmacy student

Pharmacy students also got involved, helping to identify patient-assistance programs run by drug manufacturers to offer free medications. They also are working with a network of 20 pharmacies in the area to help patients find medications at the lowest price.

“The mission of the clinic really resonated well with me,” says Keely Morris, a fourth-year pharmacy student. “I know there is a real need. By starting the clinic we are helping to ease some of the health disparities seen by Hamilton County residents.”

Faculty advisors for the clinic include doctors Megan Rich and Joseph Kiesler, both associate professors in the Department of Family and Community Medicine, along with Maria Espinola, associate professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience, and Kelly Epplen, associate dean in the James L. Winkle College of Pharmacy.

“Not only does the student-run free health clinic showcase UC student initiative and creativity, but it does so in a way that promotes an interdisciplinary network,” explains Rich. “We have students from the UC colleges of medicine, nursing and pharmacy coming together to try to solve real-world problems.”

—C. Ricks

The clinic is located in the Healing Center, Springdale, Ohio. For more information, call 513-346-4080.

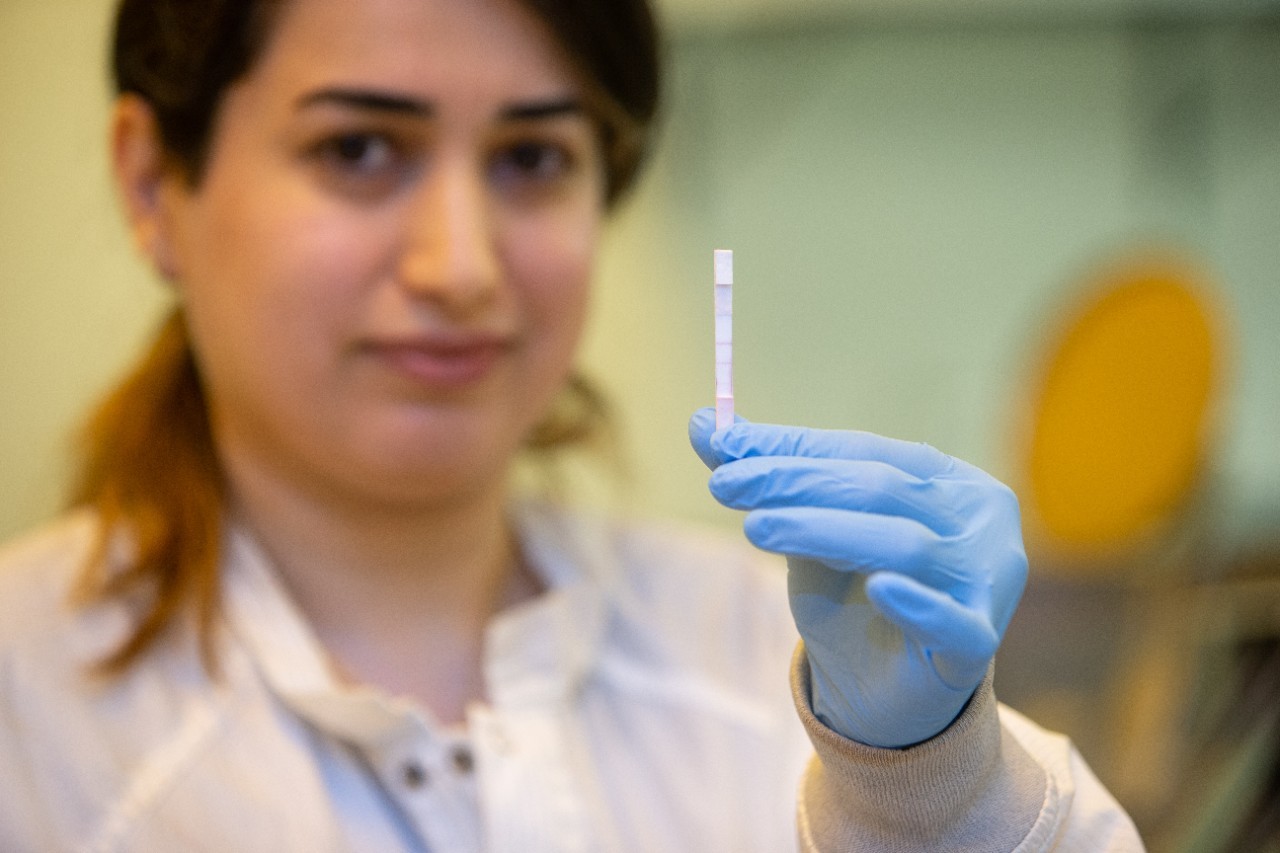

UC physics research assistant Shima Dalirirad holds a sensor in the lab of Ohio Eminent Scholar Andrew Steckl. Photo/Andrew Higley

DISCOVERY

Stress test

UC engineers create a simple test that can measure stress hormones in sweat, blood, urine or saliva

Stress is sometimes called “the silent killer” because of its stealthy effects on everything from heart disease to mental health.

Engineers at the University of Cincinnati have developed a new test to measure common stress hormones using sweat, blood, urine or saliva. Eventually, they hope to turn their ideas into a device that patients can use to monitor their health at home.

“I wanted something that’s simple and easy to interpret,” says Andrew Steckl, an Ohio Eminent Scholar and professor of electrical engineering in UC’s College of Engineering and Applied Science. “This may not give you all the information, but it tells you whether you need a professional who can take over,” Steckl says.

The device uses ultraviolet light to measure stress hormones in a single drop of fluid.

Steckl has been studying biosensors for years in his Nanoelectronics Laboratory. Personal experience helping his father with a health crisis informed his research and opinion that a home test for various health concerns would be incredibly helpful.

“I had to take [my father] quite often to the lab or doctor to have tests done to adjust his medication. I thought it would be great if he could just do the tests himself to see if he was in trouble or just imagining things,” Steckl says. “This doesn’t replace laboratory tests, but it could tell patients more or less where they are.”

The UC device has widespread applications, Steckl says. His lab is pursuing the commercial possibilities.

“Stress harms us in so many ways. And it sneaks up on you. You don’t know how devastating a short or long duration of stress can be,” says UC graduate Prajokta Ray, the study’s co-author. “So many physical ailments such as diabetes, high blood pressure and neurological or psychological disorders are attributed to stress the patient has gone through. That’s what interested me.”

UC is at the forefront of biosensor technology. Its labs are examining sweat testing and point-of-care diagnostics for everything from traumatic brain injury to lead poisoning.

“We’re device engineers at heart,” Steckl says.

— M. Miller

FEATURE STORIES

The nonprofit Village Life Outreach Project has sent hundreds of volunteers from UC to three remote villages in East Africa since it started 15 years ago, an effort that has deeply impacted countless lives on both sides of the world.

UC has invested $100,000 in Cincinnati nonprofits to commemorate the Bicentennial's impact in the community.

The new home of the University of Cincinnati’s business college is built to foster collaboration, adapt to future needs. Also featured is the brand new Allied Health Sciences building.