UC Research Examines Efforts to Combat Abortion in Israel: Financial Incentives vs. Moral Persuasion

Most pro-life movements focus their efforts on moral persuasion based on a belief in the sanctity of human life and often backed by religious conviction.

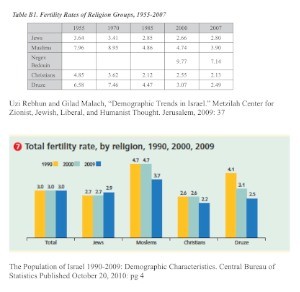

But in Israel where reproductive rights are liberal and are government subsidized in certain cases one pro-life organization offers financial support to continue the pregnancy of an exclusive group of low-income Jewish women for what some feel are questionable motives, that of helping to win Israels demographic race with its Arab population.

These are among the findings of Michal Raucher, University of Cincinnati assistant professor of Judaic Studies, who spent two years doing ethnographic and archival research in Israels Knesset (parliamentary) documents regarding reproductive rights.

While there, she also looked closely at Efrat, a pro-life organization in Israel that reaches out to low-income Jewish women often with large families already who are seeking an abortion for financial reasons. Raucher did participant-observation fieldwork at Efrat and helped collect bank statements and other pertinent paperwork from the women to help prove their financial hardship in order to meet Efrats criteria for their assistance.

What Raucher found was that while Efrat looks like a straightforward pro-life organization at first glance, it does differ from other pro-life organizations especially those in America. In the United States, pro-life movements are motivated by their focus on the inherent value of saving a human life. In contrast, Efrats efforts are motivated by the desire to save the future growth of the Jewish population in Israel.

Raucher presented her findings on Efrats pro-life paradoxical motives in Israel (in contrast to American pro-life movements) at the American Anthropological Association Meeting, December 4, in Washington, DC.

Rauchers research reveals that in contrast to other pro-life organizations around the world, privately funded Efrat offers financial support only to Jewish Israeli women and calls into question two primary concerns:

- Efrats moral position toward abortion as responding to competing challenges in Israeli society: pro-natalism on the one hand and the financial support that large Jewish families require on the other.

- Efrats paradoxical approach to abortion commodifies a Jewish baby for the sake of claiming it has infinite worth in the demographic war with an ever-increasing Arab-Muslim population.

THE VALUE OF HUMAN LIFE PARADOX

In an environment with socialized medicine where abortion requests are approved by the pregnancy termination committee at a rate of 99 percent each year (totaling about 20,000 abortions per year) and with many abortions government-subsidized under certain criteria, Israel prides itself on supporting reproductive rights for all of its citizens.

In contrast to Israels liberal attitude, however, Raucher demonstrates the paradox of Efrats pro-life motives, revealing specifically who they target and how they promote their efforts to potential donors.

Established in 1970 by a Holocaust survivor who felt that abortion was contradictory to increasing the Jewish population in Israel, Efrat sees their role as contributing to aliyah pnimit, or inner aliyahthe growth of the Jewish population in Israel as a form of immigration.

In an interview with Rauchers colleague Rebecca Steinfeld, an independent scholar originally from Stanford University, Dr. Eli Schussheim, director of Efrat explained that he has approached the Israeli government with the request to divert money away from external aliyah, or encouraging Jews to immigrate, and move it towards inner aliyah through abortion prevention. He says this is the only way to compete with the Arab birth rate in Israel. Schussheim says, We should imitate the Arabs; we should make higher births like the Arabs; we should reduce the abortions. This is the only way This is so simple. They are using millions of monies to bring you have them here. You have them here. You can make families happiness and joy to bring children and so on.

Since 1970, Efrat claims they have prevented approximately 3,500 abortions among Jewish women in Israel each year.

In looking even closer, Rauchers investigation revealed an even greater differential effect between Efrat and American pro-life organizations because Efrat does not oppose abortion on principle. Instead, they focus on women who seek abortions for socioeconomic reasons. They then extend the hope of some small financial security by promising her several items worth $1,200 for use in the first year of the babys life:

- Diapers

- Stroller

- Crib

- Food/milk

- Other miscellaneous items a newborn needs

Keeping in mind that Israel has socialized medicine that already takes care of all of the babys medical expenses, the newborn supplies and items from Efrat are easily seen to be an acceptable way for many of these women to consider continuing the pregnancy. The paradoxical irony, however, is that many of these women already have large families with low income and according to Raucher, in spite of Efrats help, they still eventually end up on welfare subsidy.

Although Israel initially implemented government subsidies to encourage reproduction among Jews, they later realized the strain those measures were putting on the states finances. To solve this dilemma, Israel formed a Natality Committee in 1966, which recommended creating a more conducive atmosphere for fertility, which would reverse the extremes of family limitation, and replace it with the concept of responsible parenthood, which emphasized both the social welfare and pro-natalist concerns of the government. The report recommended using pro-natalist psychological inducements, educational programs and propoganda campaigns to encourage parents to

not have more children than they could afford, but have enough to contribute to the states pro-natalist goals.

Just as Efrats pro-natalist approach is situated within reproductive politics in Israel, the connection between large families and poverty has also been part of reproductive politics in Israel. Despite the states pro-natalist agenda that encourages Jewish families to reproduce through financial incentives, Raucher explains that Israel also recognized the need to reduce family size among large, poverty-stricken families so as to ease their burden on their sizeable safety net.

Raucher argues that Efrats approachencouraging women in the lowest socioeconomic bracket to continue their pregnanciescontradicts initial motivations behind legalizing abortion in Israel.

EFRAT'S PRO-LIFE PARADOX

Given the fact that Efrat is straddling the tension between pro-natalism and

Israels growing safety net, Raucher argues they send a mixed message to their supporters about the value of human life.

Further action is required to make this image accessible

One of the below criteria must be satisfied:

- Add image alt tag OR

- Mark image as decorative

The image will not display on the live site until the issue above is resolved.

To target donors, social workers and pregnant women, Efrat:

- Publishes pamphlets with a picture of a toddler with a speech-bubble that reads, Arent I worth $1,200. (4,500 shekel)?

- Publicizes their donors as more than friends of the organization they are encouraged to think of themselves as parents of the children who benefit from their donations.

- Send notes to donors after the birth that read, Mazal tov! I am pleased to inform you of the birth of your child, acknowledging birth as shared between the parents and the donors.

- Continue letters to donors as providing an investment in Israel with a great return and dividend.

The donors support then is not just for purchasing a baby but making an investment in the demographic growth of Israel as a Jewish state. Each baby, while costing approximately $1200, seems to be worth much more in Israels demographic race with its Arab population. Raucher demonstrates how we can see this in Efrats frequently-used quote, Whoever saves a (Jewish) life, it is as if he has saved the world.

Efrat states that each baby has infinite potential in that they contribute to increasing the Jewish population in Israel, however, this serves to commodify that life.

Raucher concludes her paper by stressing Efrats paradoxical moral approach to abortion by reflecting a particular moral position, whereby abortion is acceptable and even necessary, in their words, except when done for financial reasons.

Raucher argues that Efrat is actually commodifying the bodies of Jewish babies for what they see as a larger ethical goal: the increase of the Jewish population in Israel.

In exposing Efrats tendency to commodify the fetus, Raucher hopes to bring awareness of how this ideology flies in the face of the pro-life movement globally, which rejects commodification in favor of a more humanistic, personhood view. In other words, the pro-life movement in America sees commodification as the problem, not the solution.

FUNDING FOR RESEARCH

All grants were part of a larger project on reproduction ethics broadly among orthodox Jewish women completed during her dissertation research at Northwestern University between 2009-2011.

- Fulbright Fellowship Foundation ($25,000.)

- Wenner Glen Fellowship for anthropological research ($25,000.)

- Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture ($4,000.)

- Crown Family Foundation from Northwestern U. ($22,000.)

Additional Contacts

M.B. Reilly | Executive Director, PR | Marketing + Communications

reillymb@ucmail.uc.edu | (513) 556-1824

Related Stories

Ancient Maya blessed their ballcourts

April 26, 2024

Using environmental DNA analysis, researchers identified a collection of plants used in ceremonial rituals in the ancient Maya city of Yaxnohcah. The plants, known for their religious associations and medicinal properties, were discovered beneath a plaza floor upon which a ballcourt was built, suggesting the building might have been blessed or consecrated during construction.

OTR mural centerpiece of 'big' celebration of UC alumni

April 26, 2024

New downtown artwork salutes 18 alumni award recipients who personify UC’s alumni success.

From literature to AI: UC grad shares career path to success

April 23, 2024

Before Katie Trauth Taylor worked with international organizations like NASA, Boeing and Hershey, and before receiving accolades for her work in the generative AI space, she was in a much different industry: English and literature.