The world is driven by liquid-vapor phase change

UC engineering professor gets NSF CAREER Award to fund research on liquid films

University of Cincinnati professor Kishan Bellur is captivated by evaporation — a phenomenon that is happening all the time, all around us, but few of us notice. Most liquid surfaces, for example, water in a test tube, are not flat. There is a slight curvature to it called the meniscus. As the liquid evaporates, it climbs up the side of the tube forming a very thin liquid film that is hard to see with the naked eye. Understanding the evaporation process and the behavior of these films are the focus of Bellur's latest research.

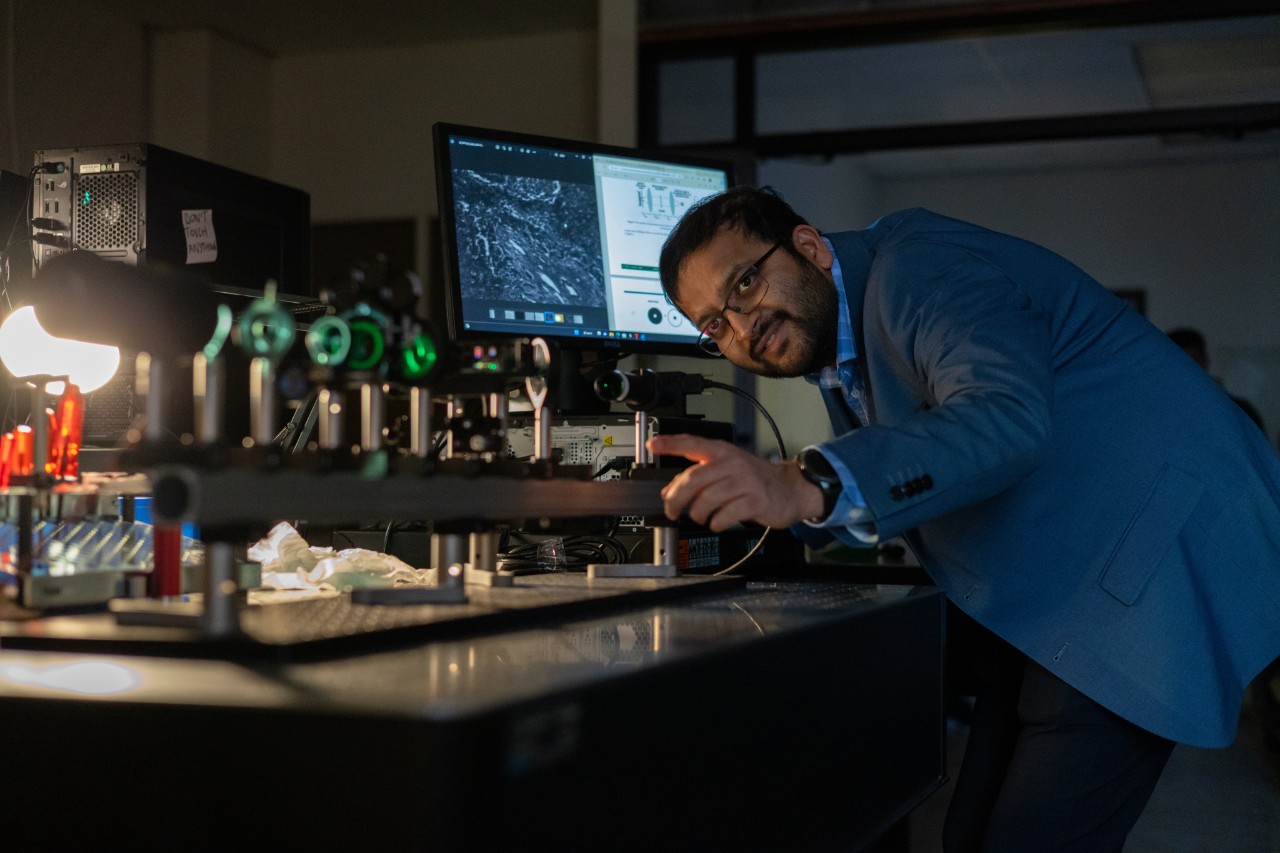

Kishan Bellur. Photo/Corrie Mayer/CEAS Marketing

Bellur, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering, received the highly regarded National Science Foundation CAREER Award to fund his research on the behavior of thin evaporating liquid films for the next five years.

Scientists are interested in studying these films because of their unique properties. Despite appearing to be stable, they actually dance around or oscillate, triggered by different factors, all of which result in a transfer of energy. This oscillation under the right conditions can move the meniscus, causing the liquid to shift up or down.

"The connection between the thin film and the rest of the meniscus is relatively unknown. That is the focus of the project," Bellur said. "We are running experiments and doing computer modeling to connect the currently unknown pieces of all length scales — from thin films to the bulk menisci."

During his doctoral studies, Bellur became interested in thin films while studying storage and evaporation of liquid hydrogen (rocket fuel) at extremely low temperatures. He realized that as hydrogen evaporates inside spacecraft tanks, it wicks up the sides of the wall and forms a thin liquid film that can oscillate. By delving deeper into the properties of these films and the wicking behaviors, a realization dawned on him.

"Digging deeper into why these films oscillate, it turns out the film stability is all about a mismatch between the evaporation and condensation process," Bellur said.

Kishan Bellur became interested in thin films during his doctoral studies. Photo/Corrie Mayer/CEAS Marketing

Evaporation is a very energy intensive process. To evaporate something, heat is applied, however, the temperature remains constant. This is one of those unique processes where heat transport does not require a temperature change. Additionally, the thin film, where much of this evaporation takes place, covers an extremely small area, making it a very efficient heat transfer mechanism in terms of square footage. Bellur and his team at the UC Lab for Interfacial Dynamics are studying how they can leverage these behaviors to develop better, more efficient heat transfer devices and make make advancements in space technology, hydrogen energy, and advanced manufacturing.

Paired with the research Bellur and his team are conducting, this NSF award also focuses on education and outreach. When Bellur was walking around a local farmers market, a realization struck him: phase change and fluid dynamics are key ingredients in cooking.

Scientific principles are all around the kitchen. For instance, the bubbling dynamics of boiling water to cook pasta, the heat transfer processes when baking a cake, the reaction of baking powder when added to a recipe; these are all examples of seemingly simple cooking tasks that are grounded in science. In short, the kitchen is a laboratory that is used by almost everyone.

Graduate students in Kishan Bellur's lab participate in meaningful research under his guidance. Photo/Corrie Mayer/CEAS Marketing

Bellur and his engineering undergraduate students are partnering with the Hyde Park Farmers Market in Cincinnati to set up a booth with demonstrations to showcase the science happening in the kitchen with marketgoers.

"I realized we could use the humble kitchen as an accessible personal laboratory to teach people about basic scientific principles," Bellur said.

The goal of this outreach is to educate the public on scientific principles that are occurring in daily life and inspire them to think about science.

In addition to the NSF CAREER project, Bellur is also involved with many facets of space research including that on the International Space Station. Currently through an NSF and Center for Advancement of Science in Space program, he is working on a unique sensor module to gather new data from a boiling and condensation experiment on the ISS. Bellur is also funded through the NASA Physical Sciences Informatics program wherein he and his team are extracting unique insights from data gathered in prior ISS experiments.

Bellur advocates for undergraduate student research and fosters student development through various programs such as NSF Research Experiences for Undergraduates and the Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation.

Featured image at top: Kishan Bellur received the prestigious National Science Foundation CAREER Award for his research on thin liquid films. Photo/Corrie Mayer/CEAS Marketing

Related Stories

Study: There might be 3 different types of ADHD

March 4, 2026

The University of Cincinnati's Melissa DelBello was featured in a National Geographic article discussing recent research she coauthored that used brain imaging to identify three distinct subtypes of of ADHD, each with its own chemical interactions in the brain.

Boosting safety in proton therapy for kids

March 3, 2026

University of Cincinnati backed startup, Range Assure, aims to make pediatric proton therapy safer by reducing radiation uncertainty and protecting healthy tissue.

UC studies supplement, therapy alternatives to treat depression

March 2, 2026

Media outlets including Cleveland.com and Cleveland's WKYC News highlighted a new University of Cincinnati clinical trial funded by an approximately $3.5 million grant from the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health to test two new nonpharmacological treatments for teens and young adults with depression.