UC engineers promising carbon-capture system

Chemical engineer devises efficient way to pull carbon directly from atmosphere

Until now, carbon capture developments have focused largely on removing greenhouse gases at their source, such as the emissions of power plants, refineries, concrete plants and other industries.

UC College of Engineering and Applied Science Professor Joo-Youp lee. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

But University of Cincinnati Professor Joo-Youp Lee said the Golden Fleece of carbon capture draws carbon dioxide directly from the atmosphere, which is much, much harder.

“The concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere are so low,” he said. “It would be like trying to remove a handful of red ping-pong balls from a football stadium full of white ones.”

He is a professor of chemical engineering in UC’s College of Engineering and Applied Science.

But Lee and his students have developed a promising system of removing carbon dioxide at about 420 parts per million from the air. And with his process called direct air capture, it can be deployed virtually anywhere.

UC postdoctoral fellow Dinabandhu Patra works at a benchtop carbon capture system in Professor Joo-Youp Lee's chemical engineering lab. Lee and his students developed an efficient system to capture carbon dioxide directly from the atmosphere. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

Power plants and transportation are responsible for about 53% of all carbon dioxide emissions. The remaining emissions are generated by industry, commercial and residential buildings, agriculture and other human activities.

“Although industrial decarbonization efforts are underway, it’s really hard to implement carbon capture in the remaining sectors,” Lee said.

The system Lee developed in his lab uses electricity to separate carbon dioxide. But he is advancing his system by using hot water instead of electricity or steam, making it more energy efficient than other carbon-capture systems. And it’s robust enough to last for thousands of cycles.

To test his system, Lee built a benchtop model about the length of a pool noodle. Air from outside the building is pumped through a canister. Lee said they can’t use indoor air because it typically contains more carbon dioxide from the people using the building.

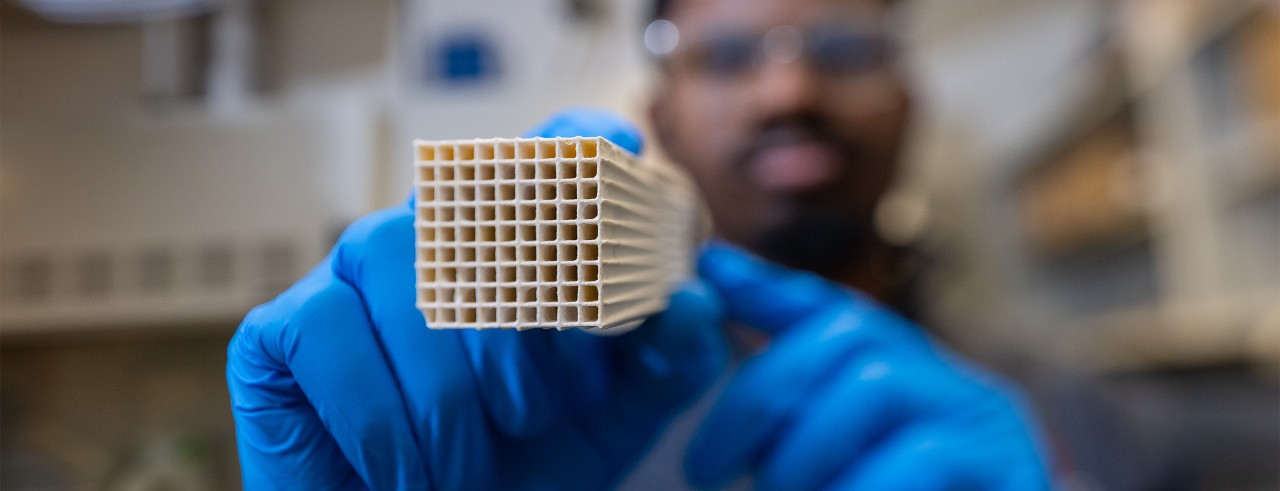

Inside the canister, the air whooshes through a honeycomb-like block wrapped with carbon fiber that Lee’s lab had custom manufactured. The individual cells of the block are coated with a special adsorbent material that Lee’s team designed to capture carbon dioxide. Gauges on the air intake and exit measure the amount of carbon dioxide in the air. When the readings on the outlet of the block begin to climb, Lee’s students know it’s time to heat the structure to remove the trapped carbon dioxide with a vacuum pump and begin the process again.

UC researchers have been able to repeat the process more than 2,000 times without seeing any decline in efficiency or degradation of the materials. But Lee said he thinks 10,000 cycles is within reach. This efficiency would make the system more economically appealing.

A larger version of the system in a climate-controlled lab pulls air from outside the building through the chamber where a honeycombed block covered in a special adsorbent traps carbon dioxide. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

Lee’s team scaled up the project in one of UC’s high-bay engineering labs, where students work on engines and other big industrial projects. Here, Lee maintains a climate-controlled environmental chamber where he can do larger-scale experiments of his concept.

They built a person-sized canister that again draws air from outside the building. But in this sealed room they can control temperature, humidity and wind speed. And they use larger honeycombed blocks the size of a loaf of bread.

“I think it’s a great project. We’re doing some real applications that can help the environment,” UC postdoctoral fellow Soumitra Payra said.

Payra is optimistic that this technology will be pulling carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere at scale soon.

With the promise of his demonstration system, Lee is hoping the U.S. Department of Energy will continue to support his plans to develop an industrial-size prototype.

“Our technology has proven to reduce the heat required for the desorption by 50%. That’s a really big improvement,” he said. “By using half of the energy, we can separate out carbon dioxide more efficiently. And we can make the cycle longer and longer.”

UC doctoral student James Akinjide holds up a honeycombed block covered in an adsorbent that captures carbon from air. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

Projects like this could be funded through carbon credit systems like the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, which indirectly pays for energy efficiency programs in 11 states.

Lee said these systems could be instrumental in addressing climate change as demand for electricity is expected to surge in years to come.

“Big tech companies like Google, Microsoft and Amazon are supporting this type of research. They will need a lot of energy to run their data centers,” he said. “In the carbon tax credit market, the more electricity you use, the more carbon dioxide you emit. So they’re buying carbon tax credits, which support the development of these carbon-capture technologies.”

Lee’s research is supported through the U.S. Department of Energy National Energy Technology Laboratory.

“I’m pretty proud of the progress of our technology development,” he said.

Featured image at top: UC doctoral student James Akinjide holds up a honeycombed block covered in an adsorbent that captures carbon from air. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

Chemical engineers in UC's College of Engineering and Applied Science are developing a more efficient carbon capture system. Pictured are postdoctoral fellow Soumitra Payra, left, Professor Joo-Youp Lee, doctoral student James Akinjide and postdoctoral fellow Dinabandhu Patra. Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Marketing + Brand

Next Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is leading public urban universities into a new era of innovation. Our faculty, staff and students are saving lives, changing outcomes and bending the future in our city's direction. Next Lives Here.

Related Stories

Student leaders find community in the University Honors Program

March 9, 2026

The Student Leader Roundtable (SLRT), a semester-long experience available to undergraduate students in the University Honors Program (UHP), offers campus leaders a vital space for discussion, connection and skill development.

Miniature marvels: A librarian’s lifelong passion finds a home at UC

March 9, 2026

In the mid-1950s Melinda C. Wells Brown moved to Cincinnati to live with her great aunt and became captivated by a collection of miniature Shakespeare plays her great aunt kept on display. Brown came to Cincinnati after the death of her father, and without her great aunt’s guidance and generosity, she would not have been able to continue her education. Her great aunt’s holistic support was instrumental during Brown’s undergraduate studies at the University of Cincinnati — where she worked in the University Library (now known as Blegen Library) and uncovered a deep passion for literature and libraries.

UC students engineer possibilities at Kaleidoscope

March 9, 2026

Cincinnati product development company Kaleidoscope Innovation hires co-op students from across UC's colleges to work on their client-focused mission.