UC Law students work to free the innocent

Fellows take a second look at cases with the Ohio Innocence Project

Caroline Waller remembers a visit from a round-faced middle-aged man.

She was a junior in high school in Mason, Ohio. The man was Dean Gillispie, who spent 20 years in prison for a crime he did not commit.

He came to Waller’s government class to share his story of wrongful conviction, imprisonment and the way he was exonerated.

“I didn’t know people who were incarcerated, so it was something I didn’t think affected me,” explains Waller. “But Dean’s experience was really eye-opening.”

The encounter planted a seed that’s now in full blossom.

Waller, a third-year law student at the University of Cincinnati, is part of a team of students working for the Ohio Innocence Project (OIP). Currently, there are 29 law students serving as either policy or litigation Fellows at OIP.

Founded in 2003, OIP is continuing its initial purpose: working to free every person in Ohio who has been convicted of a crime they didn’t commit. OIP’s work includes investigating and litigating claims of innocence by incarcerated people, helping develop and advocate for lasting criminal justice reform through legislation, educating the public to be sensitive to systemic problems in justice, rallying for change and helping wrongfully convicted individuals regain their lives and rejoin society.

“OIP is unique and offers something that other schools don’t have,” says Waller.

So far, OIP has exonerated 43 people who served collectively more than 800 years behind bars for crimes they didn't commit. Gillispie, now 60, served 20 years after being wrongly convicted of rape until OIP helped clear his name.

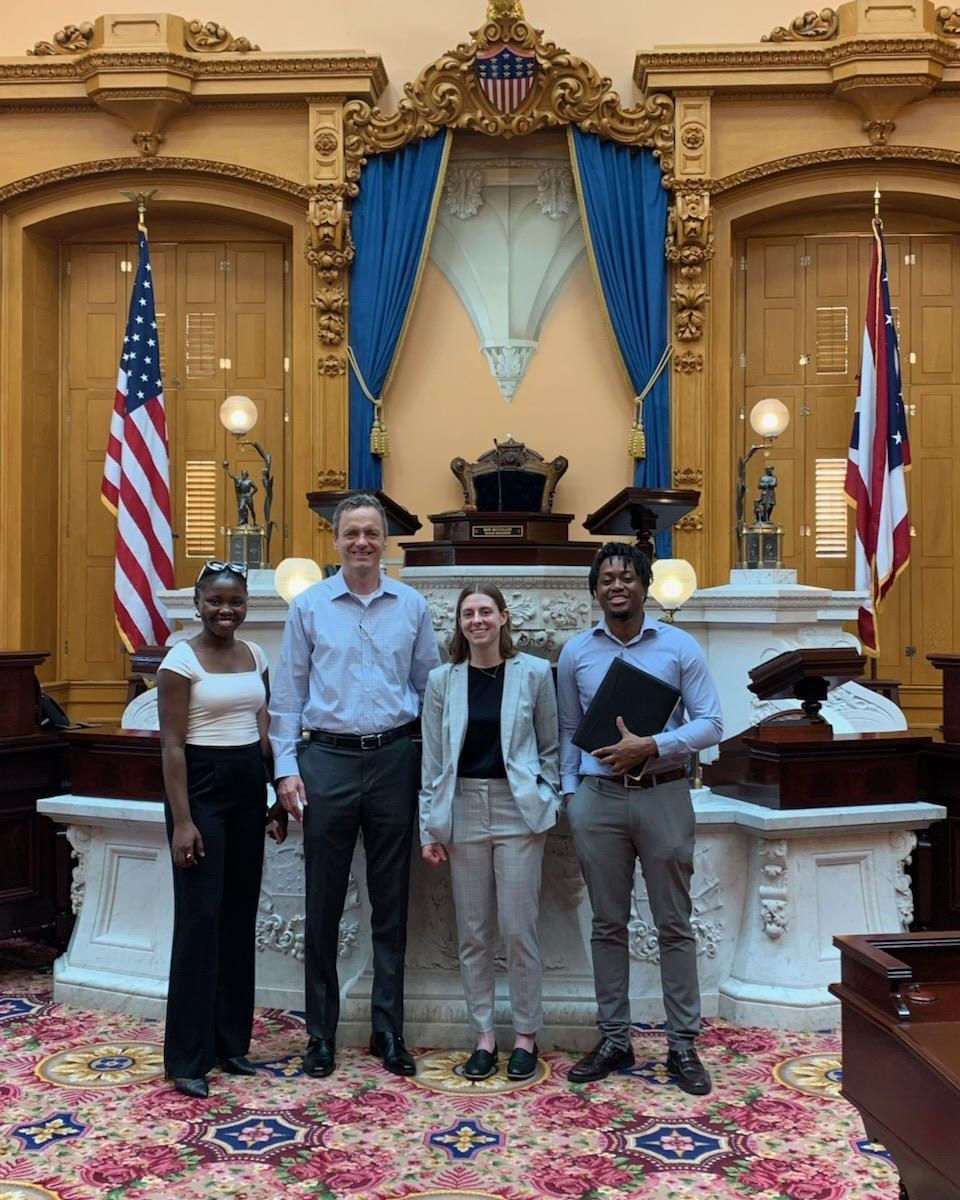

UC Law student Adesewa Adeyefa is shown with Judge Zachary Saunders from the Athens County Probate and Juvenile Court along with Caroline Waller and Kofi Agyepong. Photo provided.

“Law students are the core of the Ohio Innocence Project,” explains Brian Howe, a clinical law professor at UC’s College of Law and OIP attorney. “For students working in OIP’s legal clinic, they are the ones digging into old records, interviewing witnesses and helping to draft legal filings. For every OIP client, you can point to a handful of law students and know that without those students, an innocent man would still be in prison.”

OIP Fellows gain a wealth of hands-on experience. Under the supervision of an attorney, they review applications from incarcerated people to determine if any of those people is innocent and if that innocence can be proven in court. Students examine case files and review public records, learning how to perform legal research in a very real setting.

“OIP owes its success to the law students who are the first ones reviewing applications and tracking down information,” explains Howe. “It’s not every day that students get to have this kind of real-world impact.”

Most OIP Fellows work directly with clients and potential clients. They visit them in prison one or more times in the course of the fellowship. If a case comes to litigation, students handle the court filings and assist OIP attorneys. The Fellows work 40 hours per week during summer months and receive a small stipend. During the academic year they work 10 hours a week and get class credit.

“I think it is something that stays with them,” says Howe. “Former students will often ask about the cases they worked on, and they often remember little details about a case they worked on ten years ago.”

Laying the foundation for exoneration

It’s the overlooked details of a case that often matter for individuals experiencing wrongful conviction.

Desperate clients learn of OIP’s work from family or other prison inmates and reach out via phone or letters. They are sent an application to fill out with details about their case, and Fellows often help decide what cases might have the best chance of successfully freeing an innocent person.

Law student Waller spent a year as a litigation Fellow and during the summer she started doing work as a policy Fellow. She worked alongside Adesewa Adeyefa, a second-year law student at UC who has practiced law in her native Nigeria, and Kofi Agyepong, a third-year law student, who served as a litigation Fellow last summer.

“We work in teams of two in the legal clinic and each Fellow will take a look at the same case and do it independently so we are reaching our own conclusions,” explains Waller. “We find information online about cases from news stories and read the appellate opinion to get a judge’s summary of the facts. Some cases we can easily toss out.”

Brian Howe, far right, offers support to OIP exoneree Ricky Jackson, while OIP Director Mark Godsey looks on. Jackson was among Ohio's Death Row inmates before OIP assisted in his freedom. Photo provided.

Waller says cases with guilty pleas are hard to overturn, but they are sometimes still considered. Fellows look for circumstances that would warrant further review such as where DNA evidence in a case was never tested or if evidence obtained by the state wasn’t turned over to a defense attorney.

“These are pathways to exoneration and we have something to work with,” says Waller. “As a litigation Fellow, we would look at new cases but we also investigate cases that have been open for a while,” says Waller.

“We are trusted with so much,” says Waller. “We do the investigation, and we talk to clients and third parties. Very few law school jobs actually allow you to have one-on-one experience with clients, but with OIP, every week we are having privileged calls, just me and my partner speaking with clients.

“It was amazing to see how much I learned over the span of a year,” Waller says.

OIP receives hundreds of requests for cases and typically only takes a handful annually.

Fellow Agyepong says the connections Fellows are able to form with clients are remarkable and impactful.

“You have hard truths that you are constantly having to communicate to your clients,” he explains. “But that doesn’t mean that you can’t connect in an emotional way and create a mutual understanding between a client. You’re telling them about their case, but you are also learning about what they’re experiencing. You are growing as a person. There is a real reward to the work that we do.”

One of the most important efforts for the policy team at OIP is the work to abolish Ohio’s death penalty because of the risk of executing an innocent person.. Pierce Reed, director of policy and engagement for OIP, says the best research estimates that between 3% and 5% of people on America’s death rows are innocent, but the rate might be higher in the state.

Ohio is home to 11 death row exonerees who collectively spent 216 years incarcerated for crimes they did not commit, explains Reed. For every five people Ohio has executed, one has been exonerated from death row. OIP has three clients who had been given the death penalty and are now freed.

Nationally, around 2,100 individuals are on death row. There are 196 known exonerations from death rows in the United States, adds Reed.

“OIP is the work of last resort,” says Reed. “Ohioans sometimes forget that Ohio is a death penalty state and was once prolific in executing people. The question is not whether Ohio will execute an innocent person if executions resume. It is a question of how many innocent people will die in the pursuit of vengeance against those that are guilty. There is no justice in that outcome.”

UC Law student Adesewa Adeyefa (center) is shown with Caroline Waller and Kofi Agyepong in OIP's office. Photo/Joey Yerace/University of Cincinnati.

A small group of people make the rules

Adeyefa practiced law in her native Nigeria before coming to the United States to study for a Master of Studies in Law at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign before starting on her juris doctor degree at the University of Cincinnati.

“OIP is very personal to me,” she explains.” First, coming from Nigeria where the justice system is in the imperfect stage with too many wrong things happening is one of the reasons I decided to go to law school in Nigeria.

“My dad experienced something similar where he was randomly picked up by police officers at our house for something he had nothing to do with,” Adeyefa says. “I was a teenager then and there was nothing I could do but watch my mom in anguish over the situation my dad was in. We had to deal with that for several weeks, and it was traumatic. I thought about how I could prevent this from happening.”

She says UC has OIP which caters to people like her father but on a bigger scale. She also sees some disheartening similarities in the Nigeria and American justice system: false or coerced testimonies and police corruption that lead to wrongful convictions.

Adeyefa found enlightening her first visit to the state Capitol in Columbus to meet lawmakers and their staff. She knew these were the people who could put policies in place that could impact the lives of individuals wrongly accused and convicted of crimes.

OIP Fellow Adesewa Adeyefa joins John Barron, chief of staff and general counsel for the majority caucus in the Ohio Senate, and Caroline Waller and Kofi Agyepong in the Ohio Senate chambers. Photo provided.

“I had the opportunity to visit the rooms where the sessions actually take place where people lobby for the law they want and where people speak on behalf of the laws they want,” Adeyefa explains. “That was really eye-opening for me seeing how much can happen in such a small room.

“You get a chance to see how many life-changing things can take place in such a small room enacted by such a small section of people,” Adeyefa says. “It was very mind blowing for me.”

Policy fellows are now building relationships with lawmakers and their staff and monitoring events that occur daily in the Ohio Legislature.

“A typical day looks like us keeping abreast of any kinds of developments that come up in the State house,” explains Agyepong.

Adeyefa says she conducts research on various House and Senate members to know their viewpoints to make sure OIP knows who might side with their efforts. Abolition of the death penalty, the introduction of a bill allowing Ohio to use nitrogen hypoxia to execute prisoners, maintaining proper access to public police records and creating pathways for exoneration for the wrongly convicted are all areas of legislative interest for the OIP Fellows, explains Agyepong.

He says seven bills have been talked about or argued inside the Ohio state house generating more than 2,000 pages of text that must be reviewed. It means Fellows have to decide how to advocate for changes in the bill and how the State Supreme Court might rule or interpret a new law.

“OIP is opposed to the death penalty and wants a permanent stay of execution for individuals,” says Agyepong.

“The prosecution, the state, the jury system or conviction and sentencing guidelines don’t always bring about an accurate result,” says Agyepong. “And so whether it’s through coerced testimony, jailhouse snitches or DNA evidence, there are many ways in which a person who is innocent can find their way in the criminal justice system or worse can find their way onto death row.”

Featured top image shows Kofi Agyepong with OIP's Pierce Reed and Caroline Waller and Adesewa Adeyefa. Photo/Joey Yerace/University of Cincinnati.

Impact Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is leading public urban universities into a new era of impact and innovation. Our faculty, staff and students are saving lives, changing outcomes and bending the future in the direction of our city and state. Next lives here.

Related Stories

Back to School 2025: UC’s sustained growth

August 25, 2025

The University of Cincinnati will continue to see growth in enrollment as classes begin Monday, Aug. 25, with a projected 54,000 students — a 1.4% increase over last year.

Working towards sustainability at Michelman

September 23, 2025

UC graduate student Nishat Sultana describes her experience as a Sustainability Industry Fellow at Michelman, organized by the Center for Public Engagement with Science (PEWS).

University of Cincinnati named one of the inaugural 'Power 25'

November 14, 2025

The Cincinnati Business Courier's Power 25 highlights a mix of people, companies and organizations that are behind efforts to add population, raise Cincinnati’s profile, create jobs and contribute to the region’s economic strength and vibrancy.