UC study: Spiders risk exposure for love

Spiders that pretend to be ants keep their spiderly proportions to attract mates, University of Cincinnati biologists found

Spiders that pretend to be ants to fool predators have an unusual problem when it comes to sex.

How do they get the attention of potential mates without breaking character to birds that want to eat them?

University of Cincinnati biologists say evolution might provide an elegant solution. Viewed from above, the mimics look like skinny, three-segmented ants to fool predators. But in profile, the adult mimics retain their more voluptuous and alluring spider figure to woo nearby mates.

UC researchers presented their findings in January at the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology conference in Tampa, Florida. The insights are made possible by UC’s commitment to research, outlined in its strategic plan called Next Lives Here.

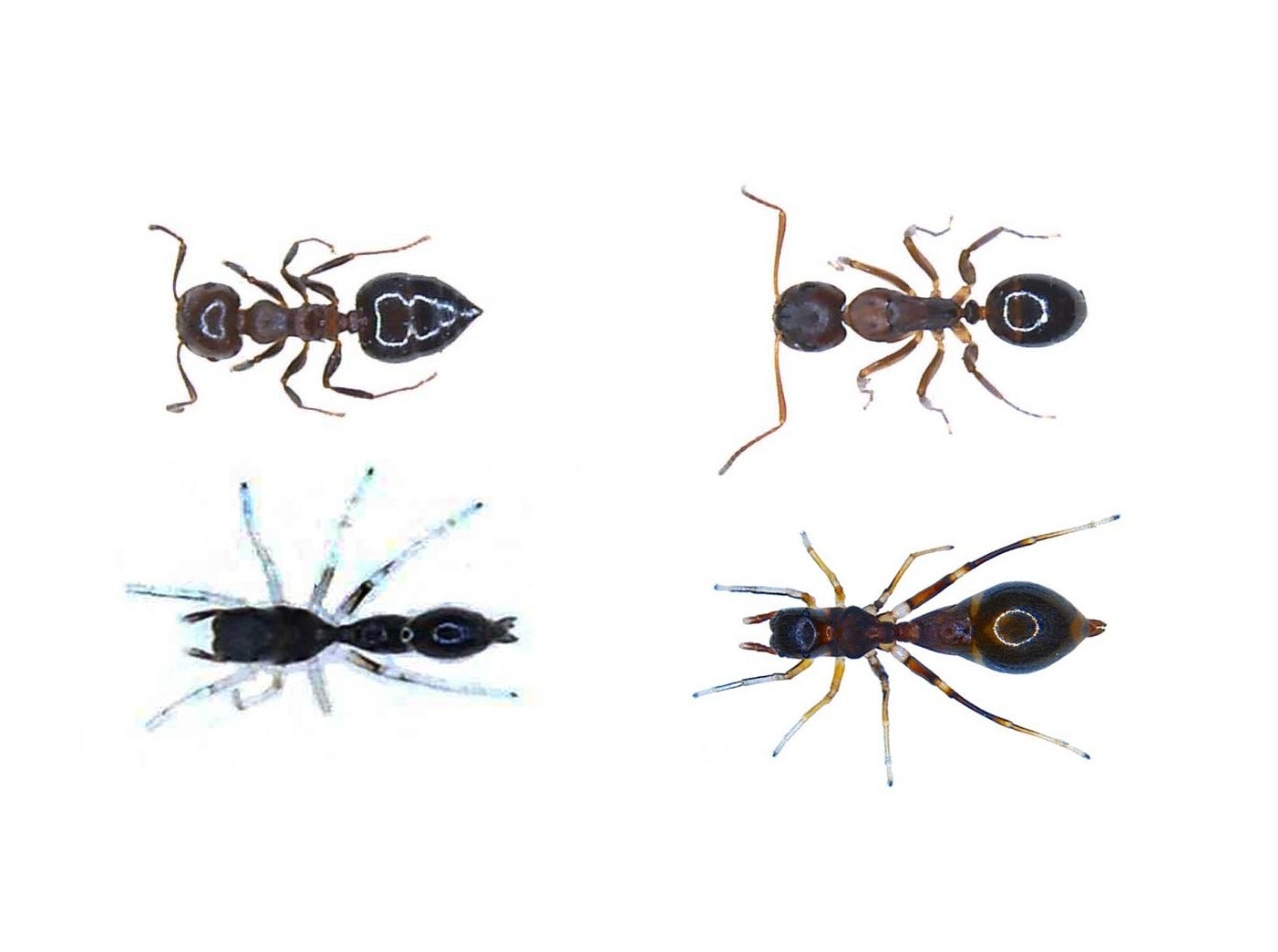

Can you tell the spiders from the ants? UC researchers found that baby S. formica spiders, bottom left, closely resembled a tiny species of ant called Crematogaster, top left, while adult spiders, bottom right, mimicked a bigger species called Camponotus, top right. Photo/Alexis Dodson

More UC biology research:

- Antarctic flies protect fragile eggs with 'antifreeze'

- UC biologists find wolf spiders see more than we thought

- UC to study spider vision around the globe

- Hungry ticks work harder to find you

- Whither the slither? UC explains how snakes move in a straight line

- UC study: Mosquitoes bite when thirsty, too

Most birds avoid ants and their painful stingers, sharp mandibles and habit of showing up with lots of friends. Try to eat one and you’re likely to get chewed on by 10 more. That’s why nearly every insect family from beetles to mantises has species that mimic ants.

By comparison, spiders are delicious and nutritious, said Alexis Dodson, a UC doctoral student and lead author.

“That’s what a lot of natural selection is all about – to convince other species not to eat you and convince members of your species to mate with you and to do so at the least cost possible,” Dodson said.

Lots of insects and arachnids mimic ants because they’re so formidable. Some plants, too, have evolved a mutually beneficial relationship with aggressive ants to discourage hungry leaf-eaters.

“Ants are distasteful,” said Nathan Morehouse, assistant professor of biological sciences in UC’s McMicken College of Arts and Sciences.

“They’re well-defended and they come in big numbers. So a lot of animals avoid them,” Morehouse said. “Unless you’re a specialist like an anteater, they’re just not a good meal.”

The level of mimicry we encounter in jumping spiders is incredibly detailed.

Nathan Morehouse, UC Assistant Professor of Biological Sciences

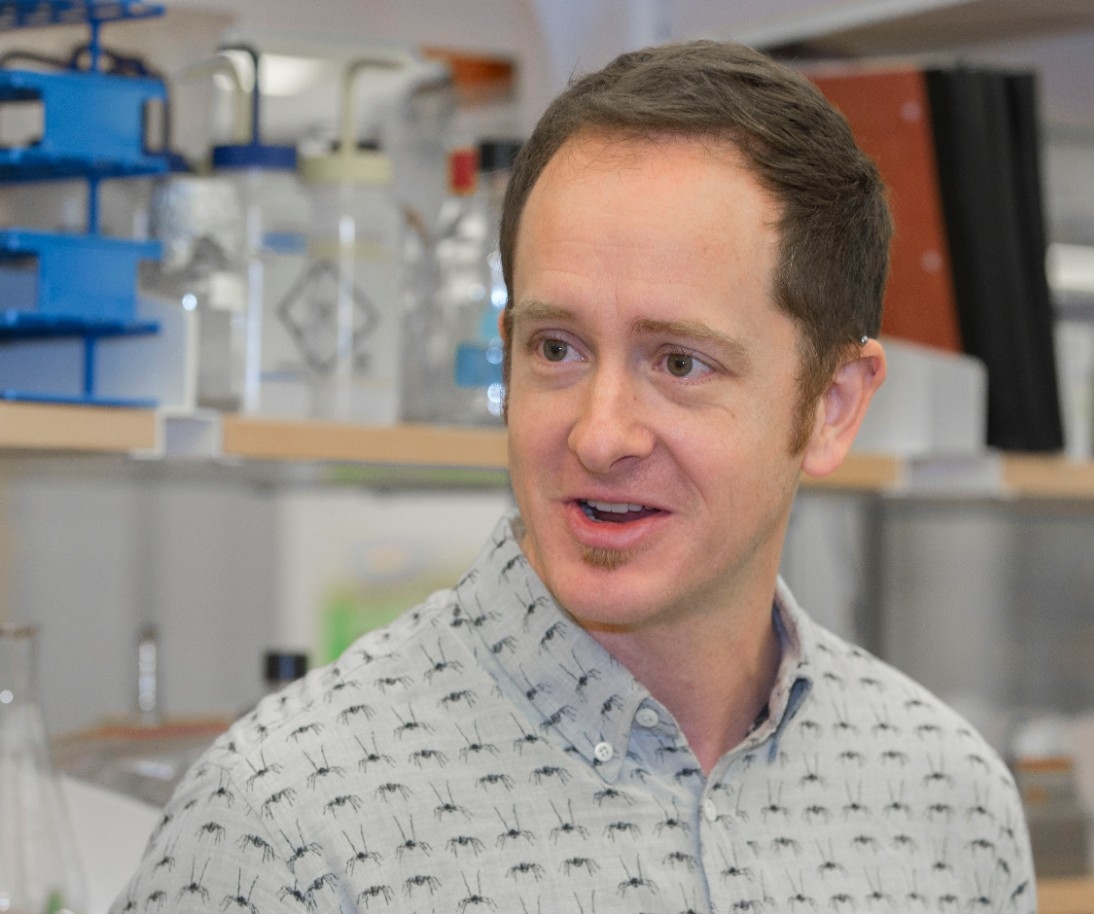

UC biologist Nathan Morehouse. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

Morehouse will use a $2 million National Science Foundation grant to study spider vision around the world. But for this study, he didn’t have to go far. He and his students collected mimic spiders by spreading a sheet under trees and whacking limbs at UC’s wooded Center for Field Studies a few miles off campus.

Spiders occupy a three-dimensional world. But whether they’re on the ground or climbing a tree, potential predators are likely to get a dorsal view, he said.

“Thinking of vantage point is essential,” Morehouse said. “From the top juveniles and adults both look like ants. And juvenile spiders look very much like ants from the side. But adult spiders shift away from the ant profile toward a more traditional spider-like profile.”

But it’s not enough to look like an ant, Morehouse said. To fool clever predators, you have to act like one, too. The spiders have enormous back legs like ants. Spiders have an extra pair of legs compared to ants and no antennae. But ant mimics will wave their small forelegs in the air like ant antennae.

“The level of mimicry we encounter in jumping spiders is incredibly detailed,” he said. “When ants follow a trail, they weave their heads back and forth. The ant is trying to cast back and forth over a chemical trail that’s hard to find.

“Remarkably, jumping spiders also perform this weaving behavior even though it has no functional significance for them,” Morehouse said. “They’re trying to be convincing actors. They’re trying to look like an ant.”

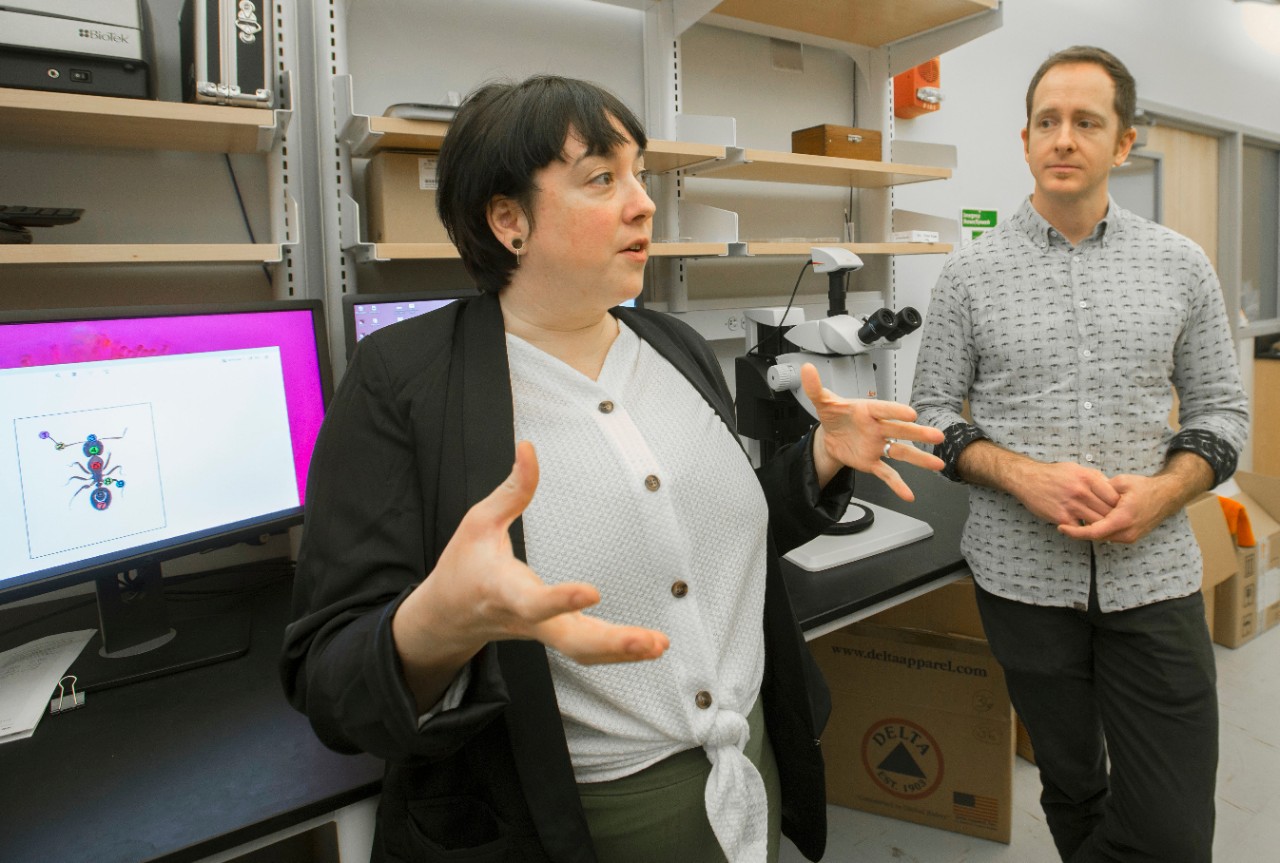

UC student Alexis Dodson, left, and UC assistant professor Nathan Morehouse talk about biomimicry in Morehouse's biology lab. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

UC researchers studied a jumping spider called Synemosyna formica found in Ohio and across eastern North America.

Jumping spiders are so named because they jump. Some can leap more than 50 times their body length. But ants don’t jump. And neither do the spiders who pretend to be ants.

In fact, it’s likely the mimics can’t jump because their antlike frame won’t allow it. Amazingly, Morehouse said, the ant mimics seem to have lost the ability to jump by copying ant locomotion so well.

“Some of it is biomechanics. They’re constrained by the loading of their body weight,” he said. “So they just sort of lurch. They’re becoming more like ants in all kinds of ways. It’s pretty neat.”

UC researchers examined how close the spiders resemble ants using an elliptical Fourier analysis, a mathematical approach that compares complex shapes. It’s an anatomical study called morphometrics.

It’s as if one says, ‘Hi, I'm not an ant' and the other says, ‘I am also not an ant.’

Alexis Dodson, UC doctoral student

UC biologist Nathan Morehouse is studying the vision of jumping spiders around the world. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

S. formica is unusual for another reason: It mimics two different species of ants during its lifetime. To make the illusion more convincing, adult spiders will mimic an ant called Camponotus, a bigger kind than the tinier black ants called Crematogaster that the young spiderlings copy.

“I think that’s the most surprising finding,” UC postdoctoral researcher and study co-author David Outomuro said. “It makes a lot of sense to mimic something that matches your size.”

Now UC researchers are studying how ant mimics communicate with each other without blowing their cover. Jumping spiders are renowned for their larger-than-life courtship rituals. Many such as the peacock jumping spider have flashy colors – iridescent blues, greens and reds – and perform showstopper courtship dances like some kind of arachnid vaudevillian.

“This is my passion project,” Dodson said. “Do they have mating rituals like other jumping spiders?”

So far Dodson has only observed what she calls “handshake” behaviors, or spiders seeming to acknowledge each other from a distance.

“It’s as if one says, ‘Hi, I’m not an ant.’ And the other says, ‘I am also not an ant,’” Dodson said. “It’s definitely there. It’s distinct from just walking around. And it’s not something I’ve seen an ant do.”

UC doctoral student Alexis Dodson is studying mimicry in jumping spiders. She found that one spider mimics two different species of ants as it grows. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

But do the mimics retain their distinctive courtship ritual like other jumping spiders? Some spiders will take these intimate encounters below ground where it’s safer, Outomuro said.

“If you do courtship outside, predators might perceive you as potential prey and the mimicry stops working,” Outomuro said.

Morehouse said the possibilities are intriguing. Perhaps, spiders behave more like ants during courtship because their antlike bodies demand it. Or maybe they borrow cues from ant behavior to maintain their protective ruse during courtship.

“Or it’s possible there are no antlike motions. When they court, they completely break character and behave like other jumping spiders,” Morehouse said. “That’s something Alexis is just beginning to understand.”

Animal mimicry has been studied extensively in many other species but not this particular jumping spider. That makes the research particularly exciting, Morehouse said.

“Alexis was first to recognize that the ant mimics look like spiders in profile. We’re really breaking new ground here,” Morehouse said. “We have to figure out how these animals can be obvious to each other but not obvious to other species.”

Featured image at top: UC doctoral student Alexis Dodson is studying mimicry in jumping spiders. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

UC student Alexis Dodson and UC assistant professor Nathan Morehouse are studying how spiders that mimic ants communicate with each other. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

Next Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is classified as a Research 1 institution by the Carnegie Commission and is ranked in the National Science Foundation's Top-35 public research universities. UC's graduate students and faculty investigate problems and innovate solutions with real-world impact. Next Lives Here.

Related Stories

Phase 1 trial tests probiotic treatment for radiation side effects in the gut

March 9, 2026

The University of Cincinnati Cancer Center’s Bailey Nelson, MD, has been awarded a $50,000 pilot grant from the Cancer Center to open a Phase 1 trial testing if a probiotic supplement can reduce gastrointestinal symptoms for patients undergoing whole pelvis radiotherapy.

Is uACR the key to cardiovascular and kidney disease prevention?

March 8, 2026

As a precision biomarker, the urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (uACR) can guide physicians toward personalized, patient-centered prevention and treatment of both cardiovascular disease (CVD) and chronic kidney disease (CKD), according to new data published in the Journal of Internal Medicine.

Driven by her own pain

March 8, 2026

Endometriosis is a painful and often debilitating disease that affects an estimated 6.5 million women in the U.S. It occurs when tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows outside of it, causing pain, inflammation and sometimes infertility. Now a University of Cincinnati College of Medicine researcher is developing what is believed to be the first at-home diagnostic test.