Dr. Eula Bingham: A lifetime of advocacy for workers

Through her research and leadership, she shaped the field of occupational safety and health

Whether it was in Washington, DC, serving as the head of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), researching in her Kettering lab space or on location at a worksite somewhere in the United States, Eula Bingham, PhD, was always working for American workers.

Bingham, who died June 13, 2020 at age 90, was an emerita professor in the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine’s Department of Environmental and Public Health Sciences. She is remembered as a tireless advocate, friend and fighter for working people.

“Dr. Bingham was fearless if she felt that someone was being harmed by either an occupational hazard or by a hazard to the community,” says Susan Pinney, PhD, a professor in the Department of Environmental and Public Health Sciences. “Her message was loud and clear, but she also was a master at timing and delivering the message. She advocated for protections for workers nationally and locally, including members of the building trades who encountered exposures to radiation, uranium, asbestos and many other substances working throughout the U.S. Department of Energy nuclear weapons production complex, both in production and cleanup. Likewise, she advocated for members of the community who lived around the Fernald plant and were exposed to uranium emissions.”

Eula Bingham, PhD

Carol Rice, PhD, emeritus professor of environmental health, echoed Pinney’s praise.

"On Saturday, the heart that embraced the rights of every worker stopped beating, and Eula Bingham slipped away. She leaves a legacy of laboratory research relevant to the workplace, health and safety policy and regulations, students who went on to improve workplaces and the environment through professional practice and research, and generations of workers empowered to limit exposure to toxics,” Rice says. “The Bingham ripples into the future are mighty: continued progress toward employment and a place of employment which are free from recognized hazards inches forward each day, as the winds blow beneath all those many wings she embolden to fly.”

The Collegium Ramazzini, a prestigious international academy of internationally renowned experts in the fields of occupational and environmental health, posted on their website following her death: “Eula Bingham was a true giant of occupational health. Throughout the 90 years of her life, she insisted tirelessly that workers had the absolute right to be safe on the job. Her thoughtful and generous wisdom shaped the entire field of occupational safety and health. Her bold and courageous actions prevented countless illnesses and injuries in workers around the world.”

Bingham served as the second president of the Collegium Ramazzini from 1992 to 1997.

When she received the academy’s highest honor, the Ramazzini Award, Oct. 28, 2000, the academy said, “Her enlightenment of students to worker safety and health issues has ensured that her hundreds of students will carry her knowledge and passion for worker protection on to many new generations assuring that worker safety and health will continue to be a key component of medical practice. Her research, teaching, dedication, leadership and advocacy will ensure that prevention of work-related diseases will continue into the future and that workers and their families will fare better because of the dedicated work of Dr. Eula Bingham.”

Raised on a farm in Burlington, Kentucky, as an only child, Bingham received undergraduate degrees in chemistry and biology from Eastern Kentucky University and then worked for two years as an analytical chemist at Hilton-Davis Chemical Company in Cincinnati before starting her graduate studies. She earned master’s and doctoral degrees in zoology from the University of Cincinnati in 1954 and 1958, respectively. From 1953 until 1961, when she joined the Environmental Health faculty, Bingham was a research associate in the department. She also did additional graduate work at the Marine Biology Lab at Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

As a faculty member, Bingham studied toxicology and chemical carcinogenesis, specifically the role of long-chain hydrocarbons in altering the carcinogenic response. She also investigated the composition of complex mixtures, petroleum, coal tar, shale oil and coke oven emissions that contributed to carcinogenic potency.

Her early work in the early 1970s as chair of the Standards Advisory Committee on Coke Oven Emissions for the Department of Labor resulted in the first U.S. standards for the protection of coke oven workers in the steel industry. She also served as a scientific and policy advisor for the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, the National Academy of Sciences, the Food and Drug Administration and the Environmental Protection Agency.

From 1972 to 1977, she was the associate director of the Department of Environmental Health before heading to Washington to lead OSHA, a young agency that had quickly become notorious for what were viewed as nitpicky rules and regulations.

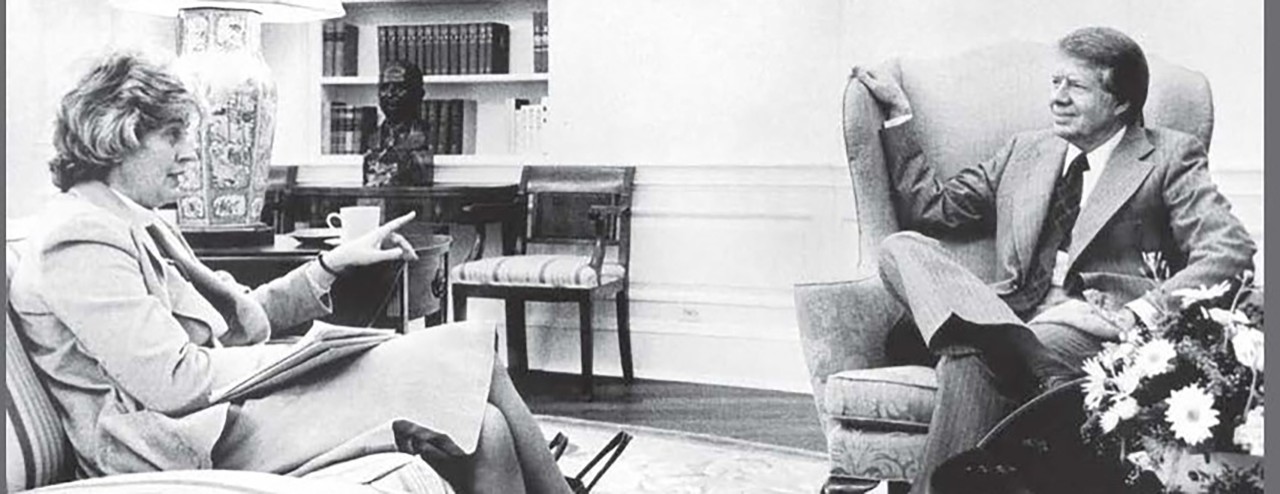

Dr. Eula Bingham while she was head of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

"I went to Washington committed. I wanted OSHA to be rid if its many nitpicking regulations and to make the agency, instead, responsible and responsive to the public in the area of public health and safety,” she said in 1981 after leaving the agency.

During her four years, she eliminated some 1,100 OSHA regulations.

She would serve as the assistant secretary of labor for Occupational Safety and Health from 1977 until 1981 under President Jimmy Carter. She was an associate professor at UC when President Carter personally interviewed her – a rarity for a sub-Cabinet appointee. Carter liked her and she was soon confirmed as the fourth OSHA leader since its inception in 1970, the first woman to lead the agency charged with ensuring the health of 65 million American workers.

Bingham quickly went to work in June 1977 and set out on a set of “common sense priorities,” focusing on serious problems in the workplace, helping small businesses comply with OSHA rules and clarifying and simplifying safety rules. She almost resigned early in her term when she fought for a cotton dust standard to protect 600,000 cotton mill workers. Economic advisors for Carter said at the time that the $625 million compliance cost was too high and argued against it. Finally, in June 1978, Carter agreed with her and the standards were accepted. And she stayed in Washington.

During her OSHA tenure, Bingham issued many new health standards for toxic chemicals. One of her significant contributions was the establishment of the “New Directions Training Program,” which created grants for small businesses and worker groups to help educate about hazards in the workplace. It was this program that served as a model for the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences in training their workers and communities.

Another accomplishment while at OSHA that Bingham believed to have been one of her most important was a regulation giving workers access to their medical records that their employers had collected on them and to see the results of workplace exposure measurements.

President Carter would recall her as “one of the best … She helped eliminate barriers to women in the workforce. Eula deserves credit as one of the unsung heroes giving women an important voice and place in our nation’s history.”

Returning to UC in 1981, Bingham served as vice president for graduate studies and research until 1990. Following that, she conducted research in worker safety, including studies on construction workers employed by the U.S. Department of Energy (DoE) in nuclear weapons production sites, which led to the creation of the DoE Former Worker Medical Screening Program.

Glenn Talaska, PhD, interim chair of the department, says that one of Bingham’s lasting legacies is the tremendous impact she had on the department.

“Dr. Bingham founded the study of chemical carcinogens and helped change the trajectory of our department. Because of her, David Warshawsky joined the faculty and this nucleus made it attractive for a famous cancer researcher, Roy E. Albert to be recruited as chair,” Talaska says.

Their work with the Environmental Protection Agency and National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) on chemical carcinogenesis led to a Carcinogenesis/Mutagenesis Training Grant for the department, which continues today. This also led to the recruitment of researchers such as Daniel Nebert, MD, Kathleen Dixon, PhD, Alvaro Puga, PhD, and others to the department, he added.

“This marked the beginning of the NIEHS Center for Environmental Genetics and the study of gene-environment interactions,” Talaska notes. “For an example of how our sciences interacted and built on each other Dr. Bingham’s own research showed that seven out of 10 workers in a local dye company making benzidine dyes developed urinary bladder cancer when less than one in a thousand people are expected to get this disease. That led to exporting the manufacture of those dyes to other countries. Forty years later, my lab found that a specific benzidine-DNA adduct was responsible for the initiation of that process in a group of Indian dye workers. That finding led to a ban of benzidine production in India.”

Bingham would serve on many additional scientific committees. In 1995, she was asked to serve on the National Toxicology Program Board of Scientific Counselors of the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. She also led a consortium that provided medical screening exams for former construction workers at gaseous diffusion plants in the Oak Ridge, Tennessee, Portsmouth, Ohio, and Paducah, Kentucky.

Bingham received numerous awards, including the Rockefeller Foundation Public Service Award (1980), American Industrial Hygiene Association’s Alice Hamilton Award (1984), was the first recipient of the William Lloyd Award for Occupational Safety from the United Steel Workers (1984) and the David P. Rall Award for Advocacy in Public Health from the American Public Health Association (2000). In 1989, she was elected to the Institute of Medicine at the National Academy of Sciences.

In 2015 President Carter said about Bingham: “I was fortunate to have many outstanding appointments in our administration, and Eula was one of the best. I always could count on her for sound and direct advice with the well-being of the American worker foremost in her mind. She helped eliminate barriers to women in the workforce and to make our nation’s workforce stronger and more productive. Eula deserves credit as one of the unsung heroes giving women an important voice and place in our nation’s history. We all should be proud of her service to our country.”

Related Stories

'Paradigm-shifting' study confirms effectiveness of long-acting HIV treatment

February 26, 2026

The results of a clinical trial involving the University of Cincinnati, recently published in The New England Journal of Medicine, show people failing HIV treatments with oral medications were able to be treated successfully using injections.

UC receives grant for AI use in medical education

February 26, 2026

The University of Cincinnati is turning to artificial intelligence to help solve a problem in medical training. The College of Medicine was awarded a grant valued at more than $1 million to use AI in advanced physician training through personalized learning.

New study links gut makeup to celiac disease development

February 25, 2026

Specific genetic architecture in the gut microbial ecosystem can shape microbial composition in ways that are potentially relevant to the pathogenesis of celiac disease, according to a study published this month in Nature Genetics.