Judge Cheryl Grant's life devoted to balancing the scales of society

A personal commitment to justice, fairness and freedom is the hallmark of the 2023 Linda Bates Parker Legend Award honoree.

From the courtroom to the community, Judge Cheryl Grant has dedicated her life to the pursuit of justice. Photo/provided

If she had turned out to be a scarred and bitter woman, weighed down by undeserved hardship and consequently accomplishing little over the years, it would have been completely understandable. But rather than be defined or defeated by the inexplicable unfairness she encountered from the very beginning of her remarkable life, Cheryl Grant, A&S ’66, Law ’73, drew on an innate positive spirit and inner willspring of grit and resolved, carving out a unique journey devoted to seeing justice done.

Grant's story is worthy of the celebration she'll receive as the 2023 Linda Bates Parker Legend Award honoree at this year's Onyx & Ruby Gala, the annual tribute to excellence in the Black UC family hosted by the University of Cincinnati's African American Alumni Affiliate. She is best known for her 20 years adjudicating cases in Hamilton County Municipal Court in her hometown of Cincinnati. Yet Judge Grant's service on the bench is just the most visible of her many roles and profound influence in an ongoing effort to balance the scales for her fellow citizens.

While the Hamilton County Courthouse is only a mile from where Grant grew up in the Lincoln Court projects of Cincinnati’s West End, the path she took to get there was hardly a straight line. Yet the uncommon traits that she demonstrated early in her youth hinted at something — someone — quite special. Most telling was a practical nature that compelled her to instantly absorb her circumstances, no matter how unjust or unfortunate, and turn her focus and efforts toward productively taking the next necessary step. While Cheryl Grant has done many things, wallowing isn’t one of them.

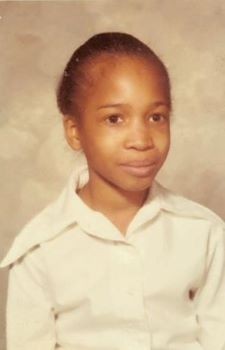

Cheryl Grant’s life was shaped by her early upbringing in Cincinnati’s West End. Photo/provided

“People say I have no feelings, that I don’t get excited emotionally,” she says, speaking of herself today but also recalling the small child she was. “And this perception has followed me. But my mother was a very pragmatic person, too. I learned very early that, rather than emote over the problem, the question is, ‘What do you do next?’ There’s a saying that you don’t let sharks see you bleed. I may get emotional but you’re not going to see it.”

Like anyone, Grant has emotions coursing through her, and given her experiences, she knows anger. She freely admits to having an edge and a tendency toward becoming inflamed in the face of racism or other forms of injustice — that’s when her anger may flash. But emotion has rarely gotten the better of her. She manages it. She channels it. She puts one foot in front of the other, doggedly moving toward something better.

“When I was five, I went to kindergarten at Washburn Elementary in the West End,” she recalls. “I walked to school, of course, and one day I got to the corner, tripped on a crack, fell down and got dirty. And I’ll never forget this — I had on my pretty new dress. Well, I got up and ran back home and told my mother, ‘I’m all wet!’ So she dried me off and cleaned me up, and I went back to that same corner and fell down again in that same place — got all wet again. Somehow, I remember thinking, ‘Things happen, Cheryl, so what are you going to do about it?’ Rather than run home to my mother crying again, I just said, ‘Forget this, I’m going to school.’”

Grant is shown with her brother and holding her younger sister. Photo/provded

This desire to “go to school” would never leave her. She largely credits the teachers who encouraged and believed in her. Role models of a sort, they helped Grant recognize education as her ladder in life. To Grant, they seemed well off in contrast to the people trying to make ends meet in the West End, so she wanted to be like them. But she also loved soaking up all they were teaching, which satisfied her curious streak. At the same time, Grant’s teachers were naturally drawn to the vast potential in the little girl with the unusually mature outlook.

The path to UC and a criminal justice career

Following her father’s passing at a young age, Grant’s mother moved her family to Cincinnati's Evanston neighborhood. As she moved through middle school and eventually Withrow High School, teachers nominated Grant for scholarships that would help her stay in school and on a path toward college, which was a rare ambition among her peer group at the time. After high school, Black girls were commonly expected to go straight into a menial job as opposed to training for a career of greater substance. Even Grant's mother felt that way. But Grant’s vision for a greater future was vindicated by proving herself during her high school years, surmounting challenging circumstances and lingering prejudice along the way. She wasn’t sure which particular path she’d take or what doors might open for her. Grant’s initial thought reflected the abiding faith that always helped sustain her, and foreshadowed a life chapter to come many years later.

“I wanted to go to divinity school first, but options were very limited — there was nothing local, and such career paths for Black women were nil,” she says. “Then I thought about food sciences because as the oldest girl in my family, I had learned to cook for my brothers and sisters while my mother worked seven days a week. But I didn’t know of any Black dieticians; how would I earn a living?” Two of her friends were going to Bennett College for Girls, a Black school in South Carolina, but even if she got her mother to grudgingly support Grant's choice to go to college in the first place, going so far away was out of the question.

“So I said, ‘Fine, but I’m going to college, and I’m going to UC,’” Grant remembers. Given UC’s demographics and culture — this was the early ’60s and UC was still a municipal university — she knew it wouldn’t be easy. Yet she also anticipated finding new opportunities on campus while sharpening her own abilities and aspirations.

“UC still had some of the segregated rules and racist attitudes the city had back then … It was in everything — housing, health care, you name it. It was a continuation of what I’d seen since I was very young, where race had shaped my life because it was always in my face. I wound up working with the university president on making progress in these areas.”

In 1967, Cheryl Grant and Novella Noble became the Cincinnati Police Department's first Black policewomen. Photo/provided

Upon graduation, Grant became a social worker so she could help find solutions to the problems that racked the neighborhoods she knew so well. She loved the work and the community center she worked from, but struggled to accept the imbalance in pay between the men and women doing similar jobs. Her brother-in-law was a police officer for the city and knew the department was looking to hire a Black woman officer for the first time in over two decades. At its core, policing was a lot like social work — helping people cope with problems. But it also stimulated Grant intellectually; she liked how it cultivated her understanding of the law and how legal issues were intertwined with social issues.

Cincinnati experienced riots in consecutive years — in 1967 when Grant was still a social worker, and in 1968 following Martin Luther King’s assassination, when Grant was on the police force. Because of what she’d been learning firsthand in her work, she understood from both sides what was happening and why.

After several years, Grant came to see that being a Black woman afforded her no real opportunity to move up in the ranks. As so often happens to those with an open mind, when one door closes, another opens.

“While I was a police officer, one of Cincinnati’s prominent attorneys asked me how I liked my job. I answered that most people I come into contact with need lawyers. So he said, ‘Well, why don’t you go to law school? Why don’t you apply to UC Law School?’ This was only about eight to ten weeks before school was supposed to start. I said it’s a little late, but if they’ll take me, I’ll go. I applied, I was accepted, and so I resigned as a police officer to go to school full-time.

“Through all of these events, I was able to get a feel for the criminal justice system, and that ultimately became my career path,” she says. “It was social worker, then police officer, then law school.”

At the time, she had no idea how much would be added to that resume in the years to come.

Divinely sent guidance in a familiar face

Judge Grant’s broad popularity is evident through her 20 years on the bench and the enthusiasm of her campaign volunteers for each of her elections. Photo/provided

The Honorable Judge Cheryl Grant of today is consciously grateful for the many diverse influencers who crossed her path and helped shape her perspectives and experiences. She takes it not as some recurring cosmic accident but as an article of faith.

“I always felt that God has shown favor to me because He placed people in my life who took an interest in me,” Grant says. One of those people she feels has done God’s work, with Grant and in society more generally, is the woman whose name is on the award she is receiving this month from her alma mater.

Linda always wanted to open doors for Black women, and I worked with her in organizations where we could do that.

The Honorable Cheryl Grant, A&S ’66, Law ’73

“I lived in the projects until my father passed, and Linda Bates Parker lived in the walk-up right across from Taft High School,” said Grant of the area where TQL Stadium, the home of soccer club FC Cincinnati, stands today. “We grew up together.”

Parker would eventually go to the University of Dayton while Grant, who was a year behind Parker in school, attended UC. Upon graduation, Parker returned to Cincinnati and worked in one of UC’s residence halls, which rekindled her strong friendship with Grant. They never stopped being, for all intents and purposes, sisters with similar passions and values.

“Linda always wanted to open doors for Black women, and I worked with her in organizations where we could do that,” Grant says. “Whenever there was a speaking opportunity, she would ask me to speak. She would say to people, ‘Can we talk?’ which became the name of her biannual conference to promote dialogue between women of different races and experiences. Parker worked tirelessly to help Black women prepare for a corporate world that had been traditionally closed to us. She gave me a sounding board and the freedom to deal with those challenges that I faced in Cincinnati trying to carve out a career. She was all about opening doors, encouraging communications.”

Grant fondly remembers Parker as a coach and a peer who did more for her than anyone else — a relationship that flowed from their history and personal closeness. Grant had known Parker's mother well from back in the neighborhood. She was there when Parker married her husband, Breland. She happily put her cooking and baking skills to work fixing Christmas dinner for Parker and Breland for many years. It was like extended family. And Grant was there when Linda founded Black Career Women Inc. in 1977 to provide career counseling and networking that facilitated the professional success of its constituents.

“There wasn’t anything she did that she didn’t want to participate in also,” Grant says. “She was with me every step of the way. No one did more for me than Linda did. She was at my sister’s funeral when she told me of her terminal cancer diagnosis. Later, she told me that a scholarship fund was established at UC in her name, and that she wanted me and two other close friends to see that the fund was endowed so that new generations of students could benefit. We all felt that was the least we could do for this great woman. Linda was just special.”

All rise: Judge Grant enters the courtroom

In July 1996, the Democrat candidate for Hamilton County Municipal Court Judge, District 3, dropped out of his race against a sitting Republican judge just a few months before the election. Grant was approached by her friend William McClain, Cincinnati’s first Black city solicitor and Hamilton County Common Pleas Court judge and a legend in the local legal community, who asked her to take the previous candidate’s place, believing she had a real chance to win.

“He was my mentor, and he’d been following me since I was a second-year law student,” Grant says. “He took me under his wing. He told me I could do it, and that I needed to do it. I said OK, I’ll do it.” Then Grant chuckles, noting the recurring pattern that had by then become familiar in her life — “I’ll do it.”

The newly elected Judge Cheryl Grant is sworn into office in the Hamilton County Courthouse in 1997. Photo/provided

She followed through, losing the election in a predominantly Republican district by a mere 800 votes, which says made her “the personality of the year” for doing so well. She ran for a judgeship in District 2 the following year and won, becoming the first Black woman on the Hamilton County Municipal Court bench. It was an arrival of sorts, placing Grant in a position where her legal mind and innate pragmatism were combined with the lessons learned from previous jobs and an upbringing where she felt the sting of needless injustice. Voters would return her to the bench regularly until her retirement in 2017.

Judge Grant, shown here in 2005, ruled on a wide variety of cases during her 20 years on the Hamilton County Municipal Court bench. Photo/provided

Judge Grant unsurprisingly relied on her faith as she wrestled with the vexing questions arising from the often-agonizing cases brought before her. She earned the reputation for being a fair-minded jurist who does her best while recognizing her limitations.

“I had to learn that I can’t be God, I can’t do His work — I have to do the human side of it, and the human side makes errors,” she says. “I had some really horrific cases in court that involved a lot of hurt. I wanted everyone involved to feel that I had valued them as a person — the victim, the defendant, the families. You deal with people with addictions, mental illness and incidents where children had been abused — that was my biggest struggle. You weigh all the factors and try to make the right decision. My faith helped me understand that my decision might be wrong, and I told defendants that there were other levels of court that could review the case and see if they supported my decision or not. But I gave what I thought was my best judgment.”

Twenty years was a long time in the crucible, and Judge Grant had no regrets when she stepped down.

“I felt I’d given everything I could. I relied upon prayer, trying to make the right decisions and do the right thing, often having to hold my tongue which was tough. I knew that, as a human being, I can’t resolve it all. I saw so much tragedy and knew I’d keep seeing more, but I didn’t let it get me down. I just did what I could to hopefully make somebody else’s life better.”

Retiring from the bench hasn’t meant relinquishing the obligation she has always felt toward creating a more just world, or helping others on their particular quests to do the same.

“I believe I have a responsibility for giving to others, just as I’ve been given to. So, I like to support people who are starting off in their careers, who may be having trouble with their vision of where they want to go. One of the gifts God gave me is a discerning spirit, which I try to use to help others, drawing on all of my experience. I think that’s my contribution.”

Ever since she couldn’t pursue divinity school after graduating from Withrow, circling back to make good on that desire had been a priority on Grant’s bucket list. While she was a judge, she did so, using snippets of vacation time over the course of nine years to meet the requirements to earn her Master’s of Divinity degree in 2012. She is proud of the dedication to see that through, and feels blessed for what the experience has entailed, including notably her in-service training as a hospice chaplain. Today she is an associate minister at Zion Baptist Church in Avondale.

It's a way of saying to Linda, 'You know what? We did it when so many people said it couldn't be done.'

The Honorable Cheryl Grant, A&S ’66, Law ’73

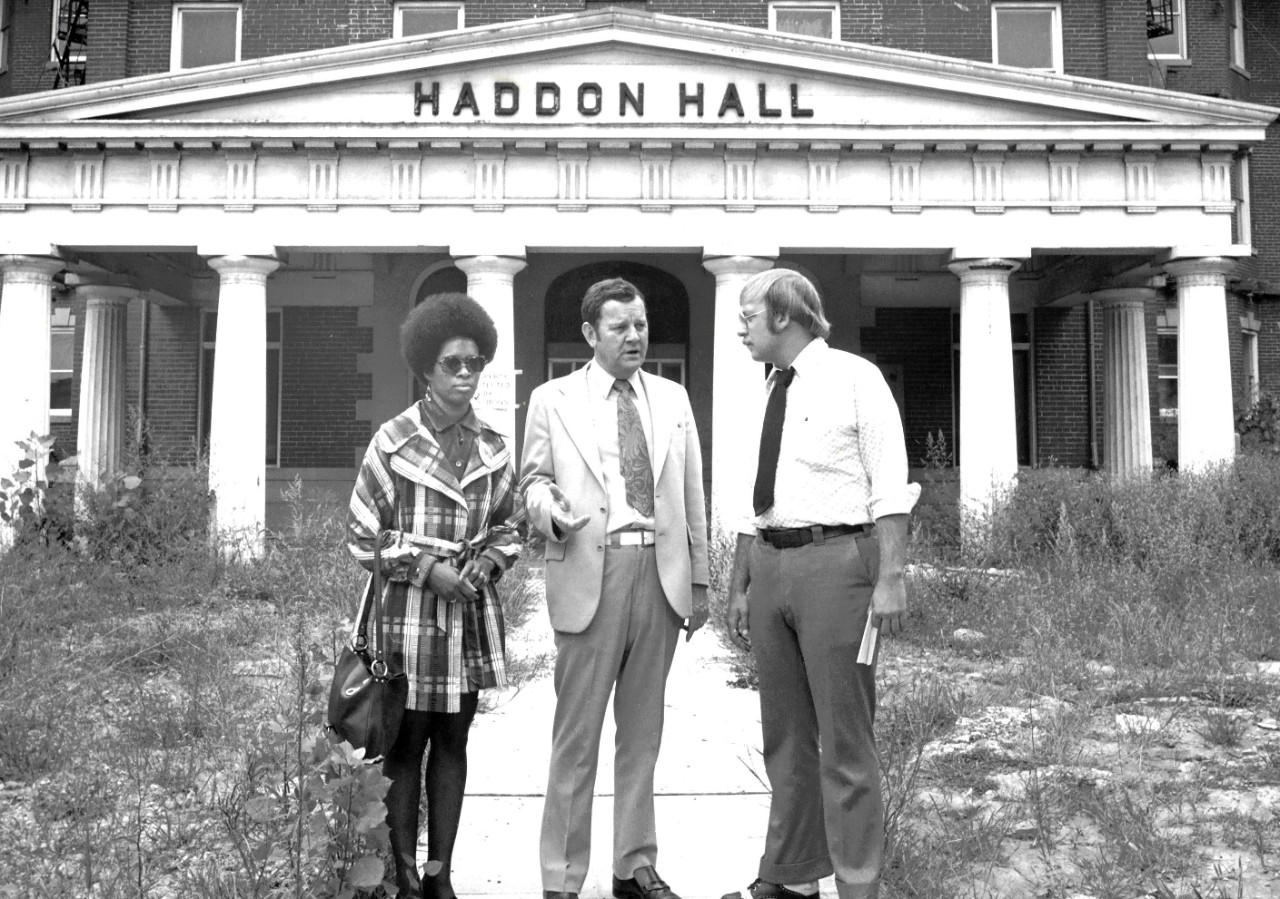

As an aide to Congressman Tom Luken, center, Grant gained valuable life lessons as well as experience in politics. Here, she and Luken are on site dealing with a housing issue in Avondale. Photo/provided

Reflecting on a life of getting things done, Cheryl Grant casts her memory back to the time when, fresh out of UC Law School, she went to work as an aide in Congressman Tom Luken’s office. A 17-year U.S. Representative from Ohio’s 1st and 2nd districts and a former Cincinnati mayor, Luken was a hard-nosed politician who reinforced a key life/career lesson for his new aide.

“He’d give you a really challenging problem, and you wouldn’t dare come back to him with, ‘I can’t do what you asked me to do,’” Grant says. “You had to come back with something to resolve the issue … ‘Don’t tell me you can’t do it, tell me how you’re going to do it.’ So, he taught me that no matter how tough the problem is, you’ve got to figure out a way to go around it, over it, under it, whatever, but you don’t give up, you don’t say it cannot be done.”

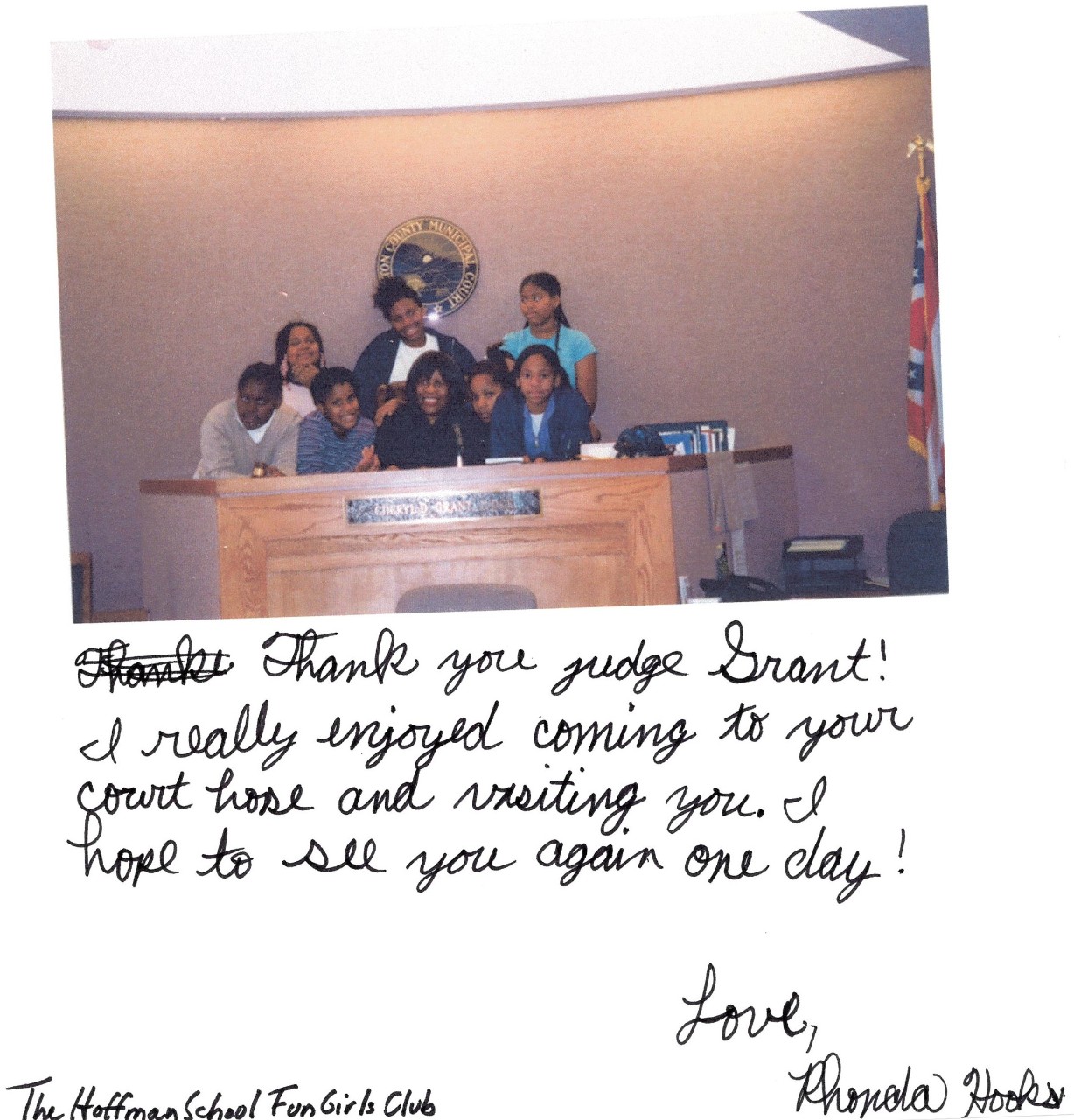

Schoolchildren had a standing invitation to visit Judge Grant’s courtroom to see how the court system worked. Photo/provided

The truth is that Cheryl Grant was born with that attitude. Her life experiences, teachers and mentors have fortified it within her, and today she believes part of the legacy she is leaving is to encourage the Cheryl Grants of tomorrow.

“Every move I’ve made in my life has taught me something,” she says. “My family taught me faith, and that when you have challenges, you don’t give up. My career choice taught me that often when you want to do something, no one else is going to support you or understand why, so once you’ve made your decision to move that way, you just keep moving.”

The only thing that saddens Judge Grant about receiving the Linda Bates Parker Award is, understandably, that her great friend isn’t physically here to see it.

“Since I learned I’d been chosen, every time I’ve thought about it, I smile because it makes me think of Linda,” Grant says. “You know, you can’t be out here like I’ve been for 50-some years and not receive some accolades and acknowledgments, but this one is very special. It’s a way of saying to Linda, ‘You know what? We did it when so many people said it couldn’t be done.’”

Maggie Ibrahim-Taney

Senior Director, Alumni Engagement

Related Stories

Love it or raze it?

February 20, 2026

An architectural magazine covered the demolition of UC's Crosley Tower.

Discovery Amplified expands research, teaching support across A&S

February 19, 2026

The College of Arts & Sciences is investing in a bold new vision for research, teaching and creative activity through Discovery Amplified. This initiative was launched through the Dean’s Office in August 2024, and is expanding its role as a central hub for scholarly activity and research support within the Arts & Sciences (A&S) community. Designed to serve faculty, students, and staff, the initiative aims to strengthen research productivity, foster collaboration, and enhance teaching innovation. Discovery Amplified was created to help scholars define and pursue academic goals while increasing the reach and impact of A&S research and training programs locally and globally. The unit provides tailored guidance, connects collaborators, and supports strategic partnerships that promote innovation across disciplines.

Blood Cancer Healing Center realizes vision of comprehensive care

February 19, 2026

With the opening of research laboratories and the UC Osher Wellness Suite and Learning Kitchen, the University of Cincinnati Cancer Center’s Blood Cancer Healing Center has brought its full mission to life as a comprehensive blood cancer hub.