After 20 years, Ohio Innocence Project steams ahead

UC Law initiative helps 42 wrongfully convicted individuals regain their freedom

Nancy Smith took a recent trip to Washington, D.C., with her grandchildren.

She rode on the Metro transportation line and marveled at the museums, the National Zoo, impressive monuments and sites of our nation’s capital.

The 66-year-old Lorain, Ohio, native now has a bit more time after recently retiring from her job as a dog groomer though she may go back to painting, a joy she found in high school and never lost.

“It was nice because I knew I could take as much time with my family, and when I came home I didn’t worry about getting up the next morning after doing all that walking,” says Smith. “It’s a lot of walking in D.C. and I didn’t have to worry about standing on my legs all day the next day.”

The mundane and ordinary feels extraordinary for Smith. She’s making up for lost time but is mostly just grateful for her freedom. Smith is one of 42 people who have been freed thanks to the work of the Ohio Innocence Project (OIP), based in the University of Cincinnati College of Law. The group of clients collectively has spent more than 800 years behind bars for crimes they didn’t do.

Nancy Smith is an OIP exoneree. Photo/Lisa Ventre/UC Marketing + Brand.

Founded in 2003, OIP is celebrating its 20th anniversary and is continuing its initial purpose: working to free every person in Ohio who has been convicted of a crime they didn’t commit. OIP’s work also includes helping develop and advocate for lasting criminal justice reform through legislation, educating the public to be sensitive to systemic problems in justice and to rally for change. It also launched OIP-u (Ohio Innocence Project University), an active network of student groups at colleges across the state.

Smith, a champion of the OIP mission, is also one of its beneficiaries.

She’s a former Head Start bus driver who in 1994 was wrongfully convicted of sexually abusing children in her care. That wasn’t true and Smith has battled daily to clear her name ever since. She spent nearly 15 years behind bars before her release with the help of OIP. In February 2022, the charges against her were finally dismissed by a judge.

For Smith, painting offered an escape behind bars. She’s a big fan of Bob Ross, an American painter, instructor and television host who created the PBS series, “The Joy of Painting.” His books helped with her technique and were a source of inspiration. She first painted with oils in prison though she had been dabbling in watercolors ever since high school.

“I thought I could paint myself out of here,” says Smith referring to her incarceration. ”I would imagine myself being out on that mountain, that lake or cabin I was creating whenever I would paint.”

“When I was in prison, the last two or three years, they had a thing called the Art Guild and we would paint for high schools, and we would do their prom decorations and backdrops,” says Smith. “In the meantime, when I wasn’t doing that I was painting pictures of landscapes for my kids. I did a time or season for when each of my kids was born representing winter, summer, spring or fall.”

Creating a strong bond among exonerees

Smith, like many other exonerees, considers OIP her family.

“When I came home I had nothing and [exonerees] made sure that I had clothes, shoes and a winter coat,” says Smith. “I came home in the dead of winter in a hoodie and a prison outfit. ”

Charles Jackson, a 59-year-old Cleveland resident and OIP exoneree, is grateful for those who freed him after spending 27 years in prison after being wrongfully convicted of murder and attempted murder stemming from a 1991 case.

Jackson’s OIP attorneys, Mallorie Thomas and Donald Caster, argued that the state violated his right to a fair trial by not disclosing evidence favorable to him. He was declared wrongfully convicted by a Cuyahoga County judge in July 2022, clearing the way for state compensation.

OIP's Charles Jackson shown upon his release. Photo/provided.

“I would like to say thank God for the Ohio Innocence Project,” says Jackson. “I wish them much success, and I want them to free all the wrongfully convicted. I will crawl through the mud anytime they call me. They restored my life and put families back together.”

“When I got out I felt like I was an intruder in other people’s lives,” says Jackson. “You are gone so long that when you come home you don't know anybody. Even your family feels like strangers. My own family, I would be in their space and I was very interested in finding my own space.”

Jackson was able to enroll in a culinary skills class after prison and to help a nephew who was especially supportive during incarceration. The nephew was forced on dialysis and would frequently call Jackson just to chat about life.

After exoneration, Jackson found he was a universal donor and gave his nephew a kidney.

“People at OIP always made sure to call me every day and make sure I was good after prison,” says Jackson. “They would check on me financially and mentally. I was going through many issues mentally, being around people and not being able to trust anyone.

“Being in prison you are feeling like your life is in danger and then you get out here and you get used to living in that danger,” says Jackson. “After all those years being in prison I felt like I left ‘home.’ It sounds crazy when I say it out loud but I felt like prison was my home.

“I was coming back to the world and it was scary. There was no internet or cell phones when I left or any of that. I came out in this big old world and people from OIP, family and close friends helped me find my way,” says Jackson.

Smith called OIP a blessing “that was bestowed on exonerees.”

“OIP kept me strong and they never let me down. I know I can trust them with all my heart. They are such good people. It’s an awesome family. That’s what we are — a family, from the students to the lawyers to the exonerees. We are one big family. Without them we would still be sitting in that prison. They brought us home. They give us hope.”

Emerging to fill a need in Ohio

Donald Caster was finishing law school at UC when he kept hearing excited talk about “this thing that was going to happen” and change the landscape for individuals wrongfully convicted.

There was a relatively new professor, Mark Godsey, and John Cranley, a Cincinnati politician, who staked out unused space in the old UC law library, explains Caster. Godsey and Cranley, who later became a Cincinnati mayor, were co-founders of the Ohio Innocence Project. Godsey is the current director of OIP.

“They were going to work on cases and eventually you started to hear that they were having some success,” says Caster, an assistant professor at UC Law and staff attorney for Ohio Innocence Project. “They would get some volunteer lawyers in the community to help out from time to time and a bunch of law students who were just sort of working through criminal defense cases. They were trying to deal with this sort of enormous demand for help because an innocence project had not existed in Ohio before that.”

Caster, as a young lawyer, kept tabs on the evolution of OIP and eventually joined as a staff attorney in 2012. He remembers attending an event in Cincinnati and learning about one of the first major exonerations in Ohio.

The New York-based Innocence Project handled the case of Michael Green, a Cleveland man wrongfully convicted in a 1988 of rape and robbery. Green was exonerated thanks to DNA evidence, and the case resonated with Caster and others in the legal community.

“I think people were seeing that there was a need for some sort of an innocence project for Ohio that was based in Ohio that would be able to work on these cases,” says Caster.

OIP Director Mark Godsey shown in the former UC Law building with OIP students. Photo/Joe Fuqua/UC Marketing + Brand.

OIP staff comb through thousands of pages of documents to vet cases for possible wrongful conviction. And Caster says since the inception of OIP, the law students at UC have been the lifeblood of innocence work.

“The litigation phase takes up an enormous amount of time, so none of the attorneys in the project have the time to touch every single piece of public record that comes through the investigative phase,” says Caster.

“The students are really the ones on the frontline,” he explains. “Obviously we do a lot of teaching and talking to them about what matters and what we’re looking for. It’s the students who will in the first instance look through these records and summarize them for us and bring the important stuff to our attention and help find those needles in the haystacks.”

Each year about 20 law students are assisting OIP.

OIP's Donald Caster. Photo/provided.

During its early days OIP focused on finding cases where there was DNA to test to exonerate the wrongfully convicted. It has since expanded to include more difficult cases that use material in public records, interviews with witnesses and non-DNA based evidence to confirm innocence.

And when DNA evidence remains part of discussion it’s because of technological advances that make use of trace material. OIP is looking at use of touch DNA such as evidence left on spent shell casings fired from a weapon or material that only a victim and perpetrator would have touched. Those cases are harder to crack.

“Ohio Innocence Project now has a reputation in the legal community across Ohio and when we come to court with something, even if there’s structural resistance, and there is always structural resistances to post-conviction cases, the judges know that we’re only coming if there is something to what we are saying,” explains Caster.

“We are in court because someone has asked us to be here and we’ve come to the conclusion that the person is innocent and that they have a legal right to relief,” says Caster. “So 20 years later, those of us who are doing this work now have the benefit of the path that others laid and the ground they broke.”

Impacting policy, staying close to exonerees

Long-time Cincinnati benefactor Richard “Dick” Rosenthal donated $15 million to the Ohio Innocence Project in 2016. He and his wife, Lois, created the Rosenthal Institute for Justice, OIP’s home within UC Law. The $15 million is used to help free wrongfully convicted individuals in perpetuity. It is helping boost recruitment of top students and faculty and supporting programming for OIP. It led to OIP occupying custom-designed space at UC Law with upgraded work spaces, offices and technology.

It also is aiding OIP’s work in another area: policy and engagement.

Beyond working on past cases of the wrongfully convicted, OIP is also proactive in its approach. OIP staff are engaging members of the state legislature about laws that impact wrongful conviction and offering professional training to judges, prosecutors, law enforcement and defense attorneys, says Pierce Reed, director of OIP policy and engagement.

OIP-u has locations at 17 universities across Ohio and a primary function is to educate people about wrongful conviction. That can mean speaking with students who will be lab workers, lawyers, mental health professionals, journalists, teachers and others to engage people across a campus and the surrounding community, explains Reed.

OIP's Pierce Reed. Photo/provided

“Students are motivated to vote and are inundated with a lot of campaigns, partisan and nonpartisan. People have to move beyond the noise of what they are seeing on television,” says Reed. “They have to be reminded they elect Ohio state Supreme Court justices, judges at every level, prosecutors and sheriffs across the state.”

“Our students’ diligence and their tenacity is critical to our success,” explains Reed. “Students have been trained how to talk with lawmakers, train other professionals and to study issues of wrongful conviction that need more attention. For example, how have women been wrongfully convicted? How have LGBTQ communities been impacted by wrongful conviction? They want to understand how language barriers can lead to wrongful conviction and what can be done about it.”

Reed says another area that’s received critical support is care for exonerees once they have been released from prison. OIP has a post-release client support team, which includes Donna Mayerson, a psychologist who provides an array of services for freed clients and also OIP lawyers, staff and students.

Her work includes facilitating organizational discussions, providing staff and students with mental health services related to trauma and providing freed clients with mental health services, education and support related to post-traumatic stress disorder and other injuries caused by wrongful imprisonment.

“What we have been able to do to help our clients gain true freedom, I always think of the first barrier is to help clients get physical freedom, get them out of a prison and that’s a lot of work and a lot of time and a lot of energy,” says Reed.

“Then the second barrier is how to help clients get true freedom in their psyche, in their heart and in their wallet. Mayerson is instrumental in helping all our clients overcome the trauma of being in prison and being an innocent person in prison.,” Reed adds.

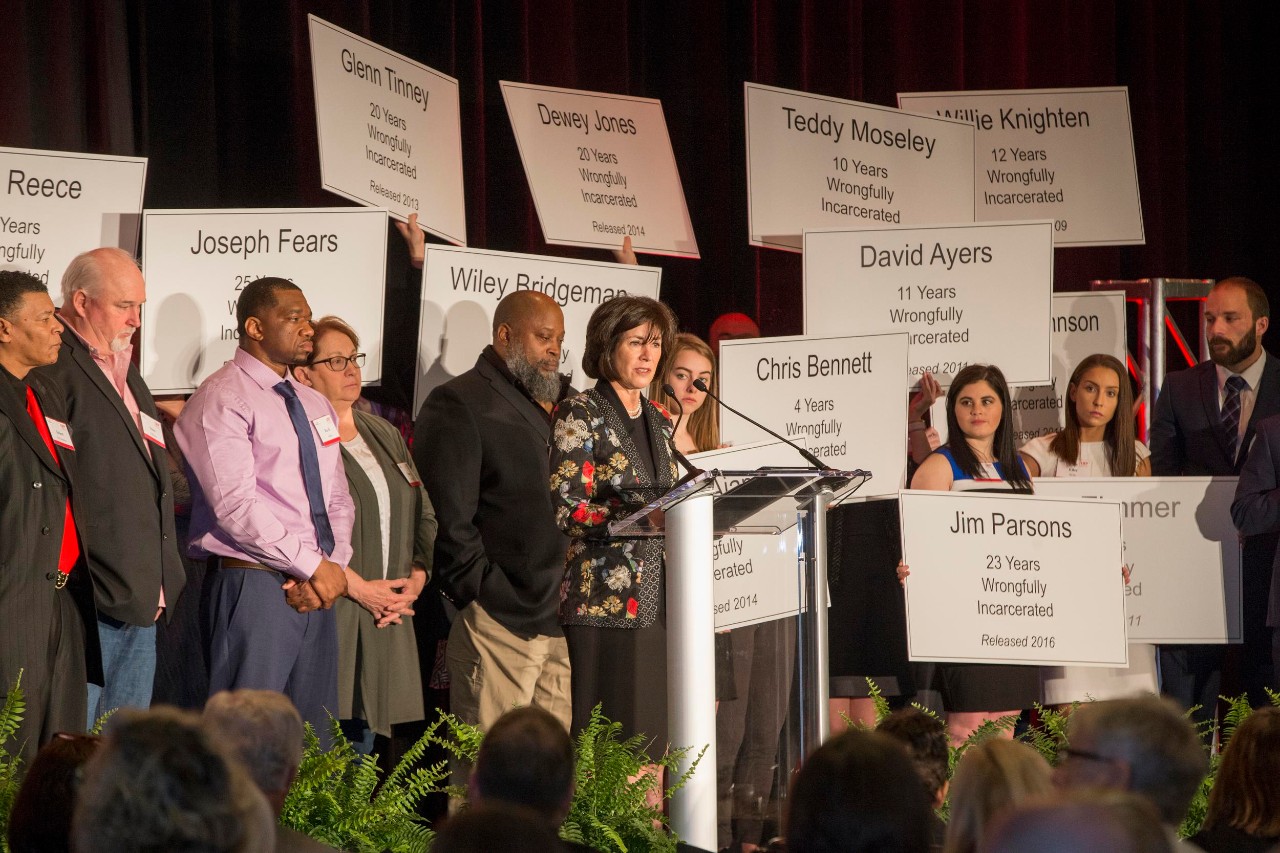

Featured top image: Jennie Rosenthal, the daughter of Dick Rosenthal, is shown at the podium of Ohio Innocence Project Breakfast held at the Hyatt Regency in 2018. To the left of Rosenthal are OIP exonerees Raymond Towler, Nancy Smith, Ru-El Sailor, Dean Gillispie and Robert McClendon. Photo/Joe Fuqua II.

Impact Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati is leading public urban universities into a new era of innovation and impact. Our faculty, staff and students are saving lives, changing outcomes and bending the future in our city's direction. Next Lives Here.

Related Stories

Before the medals: The science behind training for freezing mountain air

February 19, 2026

From freezing temperatures to thin mountain air, University of Cincinnati exercise physiologist Christopher Kotarsky, PhD, explained how cold and altitude impact Olympic performance in a recent WLWT-TV/Ch. 5 news report.

Discovery Amplified expands research, teaching support across A&S

February 19, 2026

The College of Arts & Sciences is investing in a bold new vision for research, teaching and creative activity through Discovery Amplified. This initiative was launched through the Dean’s Office in August 2024, and is expanding its role as a central hub for scholarly activity and research support within the Arts & Sciences (A&S) community. Designed to serve faculty, students, and staff, the initiative aims to strengthen research productivity, foster collaboration, and enhance teaching innovation. Discovery Amplified was created to help scholars define and pursue academic goals while increasing the reach and impact of A&S research and training programs locally and globally. The unit provides tailored guidance, connects collaborators, and supports strategic partnerships that promote innovation across disciplines.

Blood Cancer Healing Center realizes vision of comprehensive care

February 19, 2026

With the opening of research laboratories and the UC Osher Wellness Suite and Learning Kitchen, the University of Cincinnati Cancer Center’s Blood Cancer Healing Center has brought its full mission to life as a comprehensive blood cancer hub.