Study traces evolutionary origins of an important enzyme complex

MSN highlights UC Cancer Center research published in Nature Communications

MSN highlighted University of Cincinnati Cancer Center research published in Nature Communications that traced the evolutionary origins of the PRPS enzyme complex and learned more about how this complex functions and influences cellular biochemistry.

Led by first author Bibek R. Karki and senior author Tom Cunningham, the research was published July 8 in the journal Nature Communications.

The researchers focused on one of nature’s most important and evolutionarily conserved metabolic enzymes, phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate synthetase (PRPS). Most mammalian cells produce four separate PRPS-related proteins: PRPS1, PRPS2, and PRPS-associated proteins 1 and 2 (AP1 and AP2).

The field has developed no conventional wisdom as to what role AP1 and AP2 seem to be playing in PRPS enzyme function, and the team was curious why the genes encoding these supposedly “dead” enzymes would be kept around over vast evolutionary timescales.

“If a gene is evolutionarily conserved, it means it’s repeatedly favored by nature,” Karki explained. “That indicates it must be doing something important; otherwise, nature would have let it go.”

To learn more about AP1 and AP2’s potential roles within cells, the team traced the evolutionary history of each PRPS-encoding gene found in mammal cells today.

With evolution suggesting all four PRPS copies had an important role in cells, the team used CRISPR gene editing technology to knock out every different combination of the enzymes in mammalian cell lines to learn more about each of their functions.

“In all of the combinations we tried, the cells’ overall fitness declined,” Karki said. “This effect was most pronounced in cells that only had PRPS1. They simply weren’t equipped to meet cellular demands, as they grew more slowly, produced fewer nucleotides and showed defects with mitochondrial functions.”

Cunningham said because the PRPS enzymes are the only path for sugars to be converted to nucleotides to form the building blocks of RNA and DNA, there is great potential for developing personalized treatments aimed at enhancing or limiting PRPS enzyme activity.

“In the context of cancer, you may want to restrict PRPS activity so you can suppress nucleotide production and slow tumor growth,” he said. “You may want to enhance activity in the case of a nucleotide deficiency syndrome. Uncovering the basics of the complex’s architecture gives us a foothold for taking those next steps that translate our knowledge into new diagnostics and therapeutics that can improve patient health.”

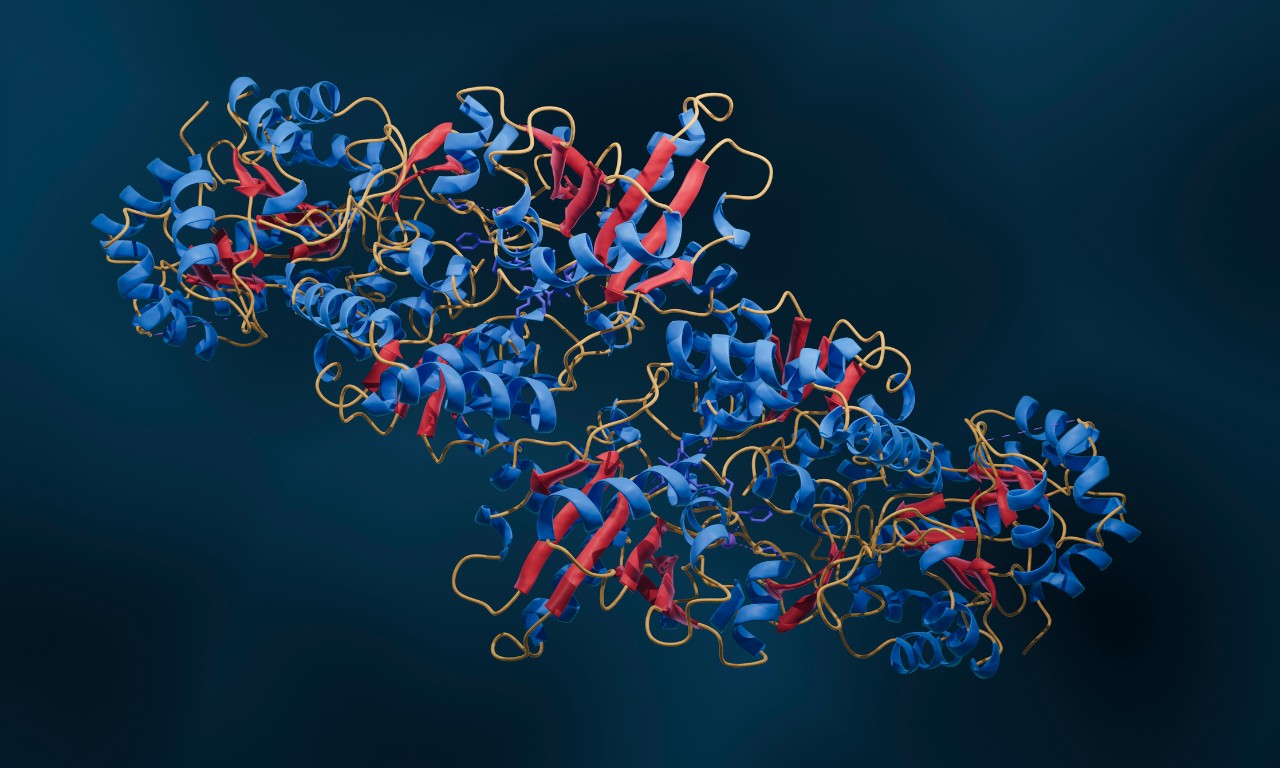

Featured illustration at top of a multi enzyme complex. Photo/Artur Plawgo/iStock Photo.

Related Stories

Love it or raze it?

February 20, 2026

An architectural magazine covered the demolition of UC's Crosley Tower.

Social media linked to student loneliness

February 20, 2026

Inside Higher Education highlighted a new study by the University of Cincinnati that found that college students across the country who spent more time on social media reported feeling more loneliness.

Before the medals: The science behind training for freezing mountain air

February 19, 2026

From freezing temperatures to thin mountain air, University of Cincinnati exercise physiologist Christopher Kotarsky, PhD, explained how cold and altitude impact Olympic performance in a recent WLWT-TV/Ch. 5 news report.