How does trauma affect your children's children?

UC researchers examine how displacement affects health of communities over generations

A University of Cincinnati professor is studying how the chemicals that manage people's genes respond when their lives are upended by natural disasters, war or other causes of sudden displacement.

UC College of Arts and Sciences Assistant Professor Kathleen Grogan is collaborating with the Batwa, an indigenous people who lived for generations in the mountainous forests of southern Uganda.

In the 1990s, thousands of people who lived in the mountain rainforests of Uganda were evicted by Uganda’s federal government to make way for new national parks created to protect some of the world’s last mountain gorillas. The displaced refugees settled in surrounding farms where they established new communities.

“I’m interested in how changes in environment affect your epigenome and your health,” she said.

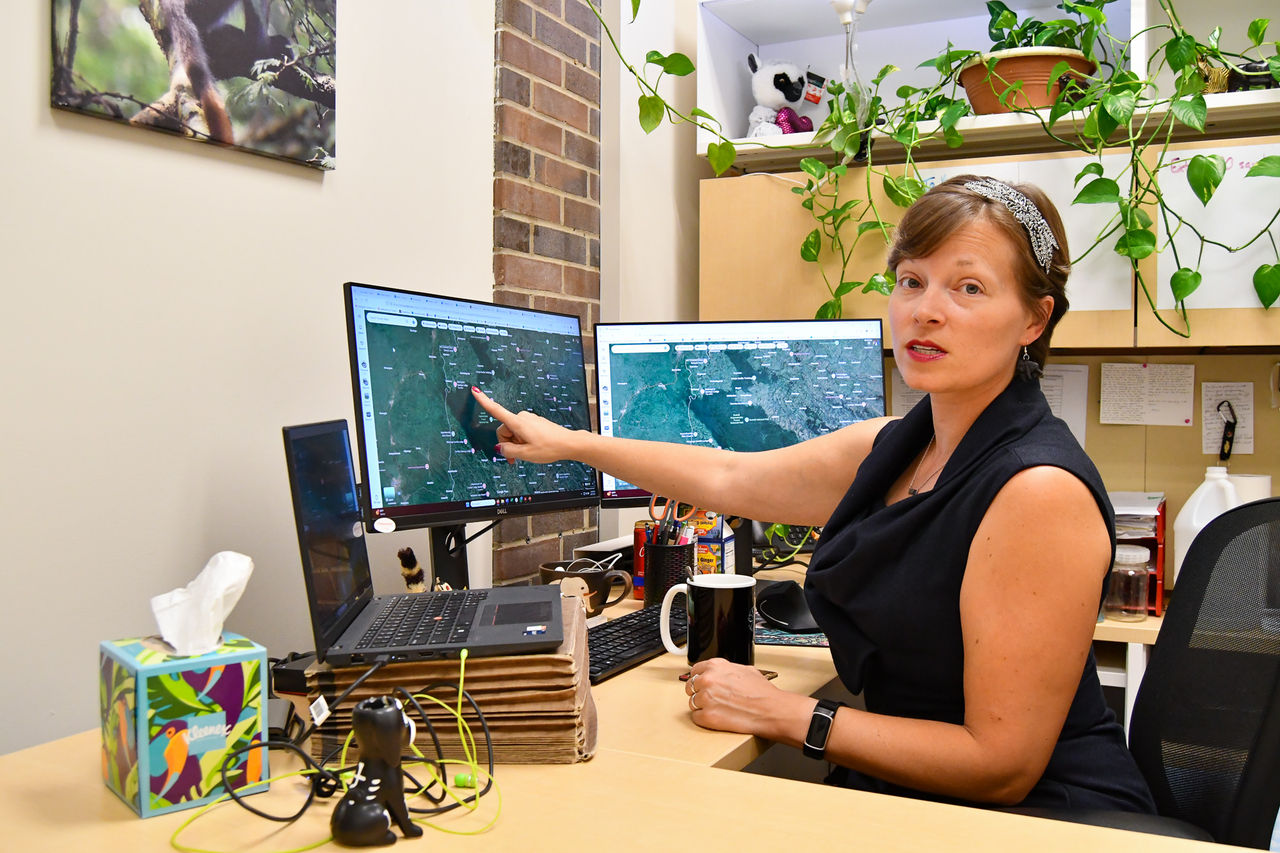

UC Associate Professor Kathleen Grogan is working with the Batwa community in Uganda to understand how displacement from war, natural disasters or other causes can trigger epigenetics that can affect people's health. Photo/Michael Miller

The epigenome is a collection of chemical compounds that modify how genes are expressed, effectively acting as a layer of instructions on top of the genome. These modifications are influenced by factors such as environment, lifestyle and development.

While the DNA that makes up our genome typically changes only through cancer and other diseases, epigenetics are the behind-the-scenes levers that activate or deactivate genes throughout our lives, often because of external factors that are still being studied.

The health effects from these changes may persist across generations. This was documented in the Netherlands when researchers discovered that the children of Dutch families that survived near-starvation in World War II had a greater risk of disease compared to older or younger siblings who were born before or after the nine-month wartime famine.

And there is evidence that these effects persist in grandchildren as well.

The Batwa now live in a genome environment mismatch because they live outside the rainforest.

Kathleen Grogan, UC anthropology professor

Grogan said the Batwa people of Uganda lived in the forest for thousands of years.

Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, which at 130 square miles is about the size of Philadelphia, and the much smaller and Mgahinga National Park, which is just 13 square miles, were established in 1991.

The terrain is rugged and steep. These mountains generate their own weather and are often shrouded in fog, giving them the name cloud forests and inspiring the title of the Oscar-nominated “Gorillas in the Mist.”

Uganda established the Bwindi Impenetrable National Park and Mgahinga Gorilla National Park to protect some of the last endangered mountain gorillas. Photo/Roger de la Harpe

Once removed, the Batwa had to adjust to life as farmers, abandoning the hunting and gathering that sustained them for generations.

“The Batwa now live in a genome environment mismatch because they live outside the rainforest,” Grogan said.

With $200,000 from the National Science Foundation, Grogan is working with the Batwa to investigate how their epigenome might have responded to these dramatic changes, which include their diet, lifestyle, activity level and even environmental factors such as pollution exposure, humidity, sunlight, temperature and elevation.

The clues Grogan discovers have implications for understanding the health challenges faced by people displaced by famine, fire, floods, war or politics around the world.

Kathleen Grogan holds up a basket made by a Batwa artist in Uganda. Families who were displaced from their traditional homes in the mountains in the 1990s had to adapt to dramatic changes. Now UC is studying how that upheaval affected their epigenetics. Photo/Michael Miller

As part of the project, Grogan will hire Batwa research assistants who will be trained to take oral histories and collect ethnographic information, which will remain with the Batwa. The Batwa will be record firsthand accounts from dozens of elders about what life was like for them in the forest.

”We hired four Batwa research assistants. And the grant will allow us to rehire them for months,” she said.

Working with people who have faced exploitation requires particular sensitivity, Grogan said. She first introduced herself to the community in 2019 and approached them in 2022 to see if they might be interested in learning more about their community health a generation after the displacement.

The research project also required ethical review from UC, Uganda’s government and the community’s hospital. More than that, Grogan said, the Batwa are the project's co-authors who helped outline the specific areas of the investigation as well as suggesting ways the project could give back to the Batwa community.

“Our community contacts are collaborators who will be on the paper and have complete veto power,” Grogan said.

The grant will allow Grogan to return to the community in 2026 and 2027 to discuss the data with the participants in person and interpret the results with the Batwa's experiences in their own words.

This will ensure that the participants have a say if they feel the project’s conclusions are offensive, problematic or could be used to discriminate against the community, she said.

“You have to make sure they’re getting more out of this than you are,” she said. “And what you do get out of this doesn’t harm anyone.”

The Batwa remain vulnerable to exploitation more than 30 years after being displaced. Uganda’s courts in 2021 ruled the government wrongfully evicted them without compensation. The government is appealing.

“The transition was not easy. We’re talking 6,000 to 10,000 people who were evicted in 1991. They were given no money and had no place to go, so they lived as squatters,” Grogan said.

With help from her research partners in both communities, Grogan took blood samples from 200 Batwa and 200 people whose families have farmed nearby land for generations to study any differences in epigenetics.

Grogan said she can’t help the Batwa return to the Bwindi Impenetrale Forest. But the project might provide evidence that the Batwa lived in the forest for many generations longer than the Ugandan government says, which could bolster their claims of wrongful eviction.

“One thing I’m grateful to UC for is I’m getting time to do this work in a way that I can be embedded in the community and learn what they want,” she said.

Featured image at top: UC Associate Professor Kathleen Grogan is studying the epigenetics of a Ugandan community displaced in the 1990s. Photo/Michael Miller

UC Associate Professor Kathleen Grogan is an anthropological genomicist who studies the intersection of genes and the environment. Photo/Michael Miller

The next groundbreaking discovery

UC is a powerhouse of discovery and impact as a Carnegie 1 research institution. From pioneering medical research to transformative engineering and social innovation, our faculty and students drive progress that reaches across the world.

Related Stories

'We’ve gone farther than any mission'

September 10, 2025

UC graduate student Samuel Hall and UC Associate Professor Andy Czaja are helping NASA use the Perseverance rover to look for evidence of ancient life on Mars. This week NASA said they might have found it.

Bazinga! UC physicist cracks ‘Big Bang Theory’ problem

December 19, 2025

A physicist at the University of Cincinnati and his colleagues figured out something two of America’s most famous fictional physicists couldn’t: theoretically how to produce subatomic particles called axions in fusion reactors.

University of Cincinnati gets $1.1M for AI physician training

January 30, 2026

The University of Cincinnati College of Medicine has received a four-year, $1.1 million grant to explore using artificial intelligence and personalized learning to improve physician education.