Agitator. Educator. Father Figure.

After nearly 50 years as UC’s conscience on matters of inclusion, campus father figure Eric Abercrumbie – lovingly referred to as 'Doc' by generations of students and colleagues – is set to retire.

Eric Abercrumbie’s secret sauce with students is quite simple.

It comes down to authentically meeting students when, where (and whoever) they are.

In fall 2015, it meant standing in the October sun on McMicken Commons surrounded by a small group of students – women and men, white and black – and framing the actions and effects of race-related bias in a way everyone in the circle of 20-somethings could intuitively grasp.

- To see the exchange, play the video below.

When standing in the circle, Abercrumbie asks, “You know any ladies that if he’s not this tall…” and here he gestures several inches above his own nearly 6-foot height “…he get no chance…. That’s your prejudice.”

What happens next is a small moment but telling.

“I feel that!” responds journalism student Patrick Murphy, who measures 5’ 6” in height.

“You feel that, don’t you!? You feel that,” repeats, nods and laughs Abercrumbie.

In looking back at this moment of both education and empathy, those 10 seconds exemplify Abercrumbie’s own growth as a bridge builder over his decades at the University of Cincinnati, consciously working toward progressive relationships with all students.

He reflects, “I’ve come to think of my years at UC not as my career but as my blessing. I was meant to be here. Reaching all students became my major end goal at UC. That’s passing on my blessing. I want to champion students, create understanding and earn allies.”

In this instance captured on video, Abercrumbie succeeds in those goals. So says Murphy, who recalls, “That moment did speak to me. It’s why I said something and responded.”

I love how he speaks with his hands and his whole body. He changes the conversation by being who he is, relatable and engaging and drawing on the energy of those around him.

Patrick Murphy, UC graduate, December of 2018

Murphy, who just graduated UC in December 2018, recollects, “I was there as a journalism student, but I also came to the teach-in on the Commons because I wanted to analyze my own biases, to examine life outside my own experiences.”

He adds, “I was excited to see Dr. Abercrumbie at that teach-in, as I’d heard him speak a few times. He is not afraid to improvise, depending on who he is seeking to connect with. I love how he speaks with his hands and his whole body. He changes the conversation by being who he is, relatable and engaging and drawing on the energy of those around him.”

And thus galvanizing opportunities for education and insight.

Agitator to educator

Eric Abercrumbie when he started working at UC in 1972.

But Abercrumbie, retiring special assistant to the president and executive director of diversity and community relations in the university’s Division of Student Affairs, recalls the long arc of growth that was necessary for him to develop as a bridge builder: “At first, when I came to UC, I got labeled as too black even by blacks because I never was reluctant to speak my mind. You have to remember that I was coming out of the ‘60s when I started here in 1972. If I thought you were racist, I’d call you out. There was a combative side to me. I like to say that when I started here, I had a 32-inch Afro and a 28-inch waist.”

In other words, at first, Abercrumbie says he had expectations that others in the campus community needed to reach out and adapt to him in his early roles as student counselor at Sander Hall and then as program coordinator for the university’s nascent Office of Minority Affairs, founded in 1976.

But over time, he came to realize much greater success by seeking to reach out to others where they were in a way that they could hear and genuinely connect with.

“He pores into you, gets your attention and asks tough questions,” according to Jeffery T. Burgin, Jr. (A&S ’97), who first visited campus as a Walnut Hills High School student. He visited campus, attending a Summer Incentive Program in the African American Cultural and Resource Center and the nationally respected conference titled the Black Man Think Tank to examine the societal challenges affecting African American men.

Burgin, who eventually served as president of UC’s Student Government and today serves as acting vice president for enrollment management and student engagement at Kentucky State University in Frankfort, Kentucky, was not initially interested in attending UC. But the connections forged by Abercrumbie and others – and the consciousness around diversity – changed his mind.

He states, “The first time I heard Dr. Abercrumbie speak, he was speaking to a group of young African American men – with a few parents there too – about the pitfalls and challenges we would face as black men in society. He actually used a curse word.

“I will never forget Dr. Abercrumbie saying, ‘Brothers don’t flunk out of school, they f--- out of school.’ I remember doing a double take. Who is this guy? Did he just say that?”

Yes, but to command attention within a group at risk in our wider society.

And the fact that Abercrumbie made a connection is evidenced by the fact that Burgin recalls the presentation 30 years later and intuitively understood and applied the message: Education is important. And to realize opportunities, prioritizing personal discipline is essential. How young African American men act will reflect on other African Americans, especially men.

Such context always influences message delivery, according to Abercrumbie, “I was speaking as a brother to other brothers and needed to command their attention to the fact that for most of them, academics was not going to be a major issue. They were smart and academically prepared. As with any student, it’s more about focus on goals, steady commitment and consistency over the long term.”

UC's Eric Abercrumbie stands at the podium during the ribbon-cutting for UC's African American Cultural and Research Center in 1991. It's now called the African American Cultural and Resource Center.

Tough love, hard-won achievements

As a candid bridge builder – as paradoxical as that description may seem at times – Abercrumbie can claim achievements and milestone that have touched generations of UC students as well as a wide spectrum of both campus and community members.

Just to name a few:

UC's Eric Abercrumbie speaks at the Black Man Think Tank, an annual conference he helped launch in 1983.

African American Cultural and Resource Center

The African American Cultural and Resource Center opened in 1991 after nearly 50 years of starts and stops toward its founding, but much of the energy toward its establishment is owed to students influenced by the programs and opportunities made available to them thanks to Abercrumbie.

The 1980s impetus to bring a black cultural center to campus occurred when Abercrumbie took students on an annual spring break tour (now a staple outing for the AACRC).

It was one stop on the 1988 tour that changed everything – ultimately leading to the founding of the AACRC on UC’s campus.

Abercrumbie recalls, “We stopped at Vanderbilt University that year, and that campus had a black center (the Bishop Joseph Johnson Black Cultural Center), and the students were like, ‘OK, we want this at UC.’”

When they returned from the spring break trip, the group of students approached Student Government, the university Board of Trustees, Faculty Senate and administrators asking, 'Will you be supportive of a black culture group?'

The students also went to Dr. O’dell Owens, then on the UC Board of Trustees, and said they’d like to have a black cultural center. Eventually, Owens and his wife donated approximately $10,000 to further the center, recalls Abercrumbie, who served as the AACRC’s first director from 1991-2013.

Local media such as Clifton Magazine covered the opening of UC's African American Cultural and Research Center.

UC's Eric Abercrumbie speaks at the Black Man Think Tank. The prevailing theme of the conference: people can be a force for change.

Black Man Think Tank

From 1983 to 1999, Abercrumbie organized a critically acclaimed conference at UC that brought together an international array of authors, journalists, political leaders, clergy, researchers, faculty, activists and students to examine societal challenges affecting African American men – and to bring about change in order to help young, black men beat the odds.

“People have power to make changes,” was the message of the Black Man Think Tank, according to Abercrumbie.

The effort generated similar gatherings, groups, choirs, and mentoring programs across the nation, often begun by high school and college students who attended the Think Tank. These included the men’s student group at OSU called The Hundred Black Men of Ohio State and groups at Florida State, Indiana University, the University of Santa Cruz and many more.

The impact of the Black Man Think Tank on the thousands who attended over the years can best be appreciated through the words of one student participant, Steven Sharp, editor of UC’s News Record. His 1999 tribute closes with the word “Halalah!” an expression of affirmation for the Think Tank’s impact on his life.

Members of the Hanarobi ensemble choir that U's Eric Abercrumbie helped create.

Three Choirs (Two at UC)

Abercrumbie has helped to found three choirs in his lifetime, living out his passion for gospel music and his roots in the black church. He helped begin a student choir as an undergraduate at Eastern Kentucky University, and helped to found two choirs here at UC because, as he puts it, “I love church. It’s one of my three fundamental foundations – church, family and education. Choirs are a bridge between church and the wider world. Music can be much more powerful than words. It makes the world more connected.”

Upon first coming to the university in 1972 as a student advisor, it was in October of that year that Abercrumbie and six students gathered around a residence hall piano to informally sing. That was the launch of the university-community contemporary, non-denominational gospel ensemble titled Hanarobi, that traveled widely from Dayton, Ohio, to Daytona Beach, Florida, all in an effort to build connections between campus and community and provide leadership opportunities for students. On campus, the group provided a Fall, Winter and Mother’s Day concert.

Wherever and whenever performing in high schools and churches, Hanarobi – comprised of UC students, faculty and staff as well as Cincinnati Public Schools teachers and members of the community – all led by Abercrumbie as choir executive director and advisor, the members served as ambassadors and role models for youth interested in college careers.

The Hanarobi gospel ensemble performed across the country.

After UC’s African American Cultural and Resource Center opened in 1991, Abercrumbie as its first director moved quickly to found the AACRC Choir in 1992 to provide inspiration – and belonging – through song.

The group travels the country and has twice earned first place in the Gospel Collegiate Choir Competition at the Gospel Today Conference. The choir has performed with and opened for not only artists but global leaders like retired U.S. Secretary of State and U.S. Army four-star general Colin Powell; actor and activist Ossie Davis; poet, author and activist Maya Angelou; activist the Rev. Al Sharpton; and many noted Grammy-winning gospel singers like Kirk Franklin, Tramaine Hawkins, Yolanda Adams, Donald Lawrence (who is also a CCM graduate) and many others.

Members of the AACRC Choir perform in the 1990s.

That choir was a big part of the reason Leisan Smith, A&S ‘ 99 and CECH, 2003, opted to attend UC: “As a high school student, I came down from Columbus, Ohio, for an Images of Color (Admissions) event, and the choir performed. The energy it had was great. I could see myself as a part of it. UC was my very first visit to any college campus, and right then and there with the choir performance closing, I turned to my mom and said, ‘This is where I want to go to school. Cancel the rest of my (campus) visits.’”

That initial connection Smith felt to the choir as a campus visitor was one she lived out as a student and still does as an alumna – crediting both the choir (where she served as the first unofficial president) and the AACRC with creating both lasting memories and vital friendships that have endured for 20 years.

“It helped me feel connected as a black student at a predominantly white school. It helped the university not feel so overwhelming,” states Smith, who today serves as director of student and community engagement at Bexley City Schools near Columbus.

It’s hard to describe if you haven’t been part of a singing group, but the depth of the felt communication in singing exceeds what’s usually possible with the spoken word, she explains, adding, “I loved the connection even with students from other schools. I can still recall our visits to Mississippi and our choir and that at The Piney Woods School performed for one another.

AACRC choir member Leisan Smith.

Smith continues, “I can still recall when my UC family and my birth family got to meet and come together when the choir performed at my home church in Columbus. It was the first time my grandmother got to see me perform as a UC student.“

Creating these opportunities for connection is why Abercrumbie worked to launch these groups, and Smith has learned to never underestimate those bonds.

She still tells the story of when her grandmother passed away several years ago in Columbus. At the funeral, Smith remarked to her mother that perhaps Abercrumbie would attend to pay his respects: “My mother even said to me, 'He doesn’t even know your grandmother.’”

But sure enough, Abercrumbie not only came, but he even spoke, according to Smith, “getting up and giving a beautiful mini-eulogy. Days later, people were still talking about how movingly he spoke of her and asking my mom, 'Who was that?'"

Who indeed.

Leisan Smith stands in front of the Village Keeper wall mural at UC's African American Cultural and Resource Center.

Spring Break Tour

Thirty-eight years ago, Abercrumbie launched a Spring Break Tour for students to travel to various areas of the southeast United States – and it was this tour that actually led to the establishment of the AACRC more than 25 years ago.

The tour provides students the opportunity to network with students at other universities and compare programming, resources, organizational structures, and also provides the UC students the opportunity to network with UC alumni. For some, it’s their first trip outside of Cincinnati, and many students leverage the tour for graduate school visits or to scout prospective cities for future employment opportunities.

Jeffery T. Burgin, Jr., and the UC Bearcat.

Abercrumbie also uses the tour to create mentorship bonds with students and to foster unlooked for and unexpected connections, including a conversation with one-time student body president Burgin, who participated in the Spring Break Tour of 1995.

States Abercrumbie, “I had such respect for Jeffery’s leadership achievements and potential, I wanted to try and bring home that the campus environment was a somewhat protected sphere. He was going to have to get a lot more serious about leadership as he moved beyond campus after graduation. It was a moment of tough love.”

Burgin recalls that same one-on-one conversation he had with Abercrumbie outside of the Sarratt Student Center at Vanderbilt: “Everyone else had gotten off the bus, and Doc asked me to stay behind. I remember thinking, ‘Why? What did I do?’”

The subsequent – and difficult – conversation became the bedrock for Burgin’s leadership role as the second African American ever to be elected study body president. (The first had been Tyrone Yates more than 20 years before.)

“What I didn’t understand at the time,” states Burgin, “Is the magnitude my role held for others. It was not only significant for me. It meant a great deal to others as well.”

Today, when I think of altruism, I think of Doc. In every way possible, he showed that we students mattered.

Jeffery T. Burgin, Jr., UC graduate and 1997 class president

"That’s where Doc focused me. Leadership was not something I could put on or take off at will. Leadership is not part time. My leadership role could never be just about me, even though the crux was about what kind of person was I going to be. It was almost a diatribe, but it was clearly motivated by altruism. Today, when I think of altruism, I think of Doc. In every way possible, he showed that we students mattered.”

Abercrumbie also recalls that conversation of 25 years ago when he advised Burgin, “You have a choice. Either you’re going to be what people say you are as a black male, or you will stand up, be a man and be a leader. Don’t talk about it. Be about it.’”

Importantly, Abercrumbie seeks to follow his own advice.

“He walks the talk,” succinctly states John Croswell, 63, president of Croswell Bus Lines, Inc., in Williamsburg, Ohio, Clermont County.

Croswell first met Abercrumbie 38 years ago when Abercrumbie came to him, interested in renting a bus for that first Spring Break Tour of 1980.

A Croswell Tours bus. Photo/provided

What could have been a simple and somewhat impersonal business transaction became much more than that over time, according to Croswell, who explained, “He has such a great respect for where we all come from as human beings. He will sit and actively listen to someone else’s side in such conversations and then move the conversation forward from wherever might be the starting point of that person. Based on that, he and I have had hundreds of hours of discussion on race relations, what is the meaning and impact of prejudice and bias in its every-day effects."

“I, in turn, have had hundreds of hours of conversation with those I know on these topics, based on my discussions with Doc. It’s been a multiplier effect many times over.”

Croswell recalls when he had to pick the bus driver that would take the wheel on that first Spring Break Tour: “That tour has some all-night drives. We drive right through from Nashville to Houston. You want to have your best driver on that type of trip. It’s a hard drive and a rough trip for the driver.”

So, back in 1980, Croswell recalls he turned to a reliable, long-time driver named Butch (Robert "Butch" Klein). Trouble was, Butch was something of a rough character, and he was admittedly insensitive to issues of race.

According to Abercrumbie, “Yes, Butch was clearly irritated to be on a bus with all-black passengers.”

Bus driver Robert "Butch" Klein.

However, both Croswell and Abercrumbie also recall that pretty quickly, Butch’s attitude did a u-turn, and he instead insisted – for the next 25 years – on being the Spring Break Tour bus driver.

“We were in the deep south and were not always treated well at some establishments. Butch saw that,” states Abercrumbie, adding that the students also won Butch over by being more than polite. For instance, they insisted on celebrating his birthday during that first trip with an impromptu party. That party became a 25-year annual tradition until Butch’s retirement.

“Butch came to love the trip. It added real meaning to his life. When the students would come back for reunions when they were doctors, lawyers or accountants and ask, ‘How’s Butch?’ That meant everything to him. It was the trip of their college lifetimes for the students. It was just that for Butch’s working life too,” recollects Croswell.

“The students had learned from Doc to take what was a business transaction and work across cultural lines or lines of race and religion to make those kinds of human connections,” reflects Croswell, who adds that what started as a commercial transaction – the renting of a charter bus 38 years ago – has also changed his life.

When asked to explain, he picks out prized momentos in his office – an autographed photo of singer Paul McCartney of the Beatles and similarly signed images of NFL players.

He states, “Most people would say that these indicate highlights of my career. They’re not. Eric transformed my life. My relationship with him is as meaningful to me as my relationship with my own father. I call Eric my life pastor. I am a better human being thanks to him.”

UC's Tom Thacker (No. 25) drives the lane during the Crosstown Shootout against Xavier. Thacker's dominance on the court inspired a 12-year-old Eric Abercrumbie who wanted to be just like him.

Born to be a Bearcat

From early youth, Abercrumbie was a stalwart Bearcats fan.

Born in segregated, rural Falmouth, Kentucky, in 1948, he was the first-and-only black player on his grade school basketball team (as well as the first-and-only black person in his Cub Scout and Boy Scout packs).

He distinctly recalls, “I always loved UC. I idolized the Bearcats. It was 1960, and I was 12 years old, and that’s the year Tom Thacker, number 25, began playing for UC. He was also a guard, and I could see myself being like him one day. The Bearcats team represented everything I wanted.”

The UC men's basketball team won back-to-back national championships in 1961 and 1962. Eric Abercrumbie idolized the champions.

Indeed, Abercrumbie’s devotion to Thacker – who was part of the storied UC teams of the early 1960s when the Bearcats won back-to-back national NCAA titles against Ohio State University – was so intense that he earned the nickname “Thack” or sometimes “little Tom Thacker” from his team mates.

And when the Bearcats third trip to the national NCAA tournament in 1963 ended in a loss to Loyola University in Chicago, Abercrumbie admits, “I recall watching the game on a little, grainy, black-and-white TV set. I was sitting next to a coal stove, and I cried and cried when the Bearcats lost. I loved Tom Thacker, Paul Hogan, Tony Yates and Ron Bonham (UC players of the era). They were everything I wanted to be. My hope and dream was to be a college basketball player like them, to come to UC and be one of those stars. When they lost that 1963 championship, I thought I would never get over it.”

Later in 1963, Abercrumbie moved to Covington, Kentucky, to attend high school in “the big city, or so it seemed to me then,” he laughs, still employing his natural athleticism as a means to fit in and seek acceptance, continuing to play basketball and run cross country.

And the proximity to the university brought him into contact with UC students, and he recollects, “There were students who I met and who I admired. They were really smart, and they went to UC.”

And it was just that chance to actually work with those smart students that initially brought Abercrumbie to UC and has ultimately kept him here ever since: “I’ve never looked for another job while I’ve been at UC. This was my community, and I wanted to transform it to be more inclusive. Parents leave their children with us, and it’s a trust and a charge I’ve always felt. I was needed. I wanted to give students a different experience than I had in segregated schools. I want to be a resource as they decide on a direction, but also help them to love UC and support this community too.”

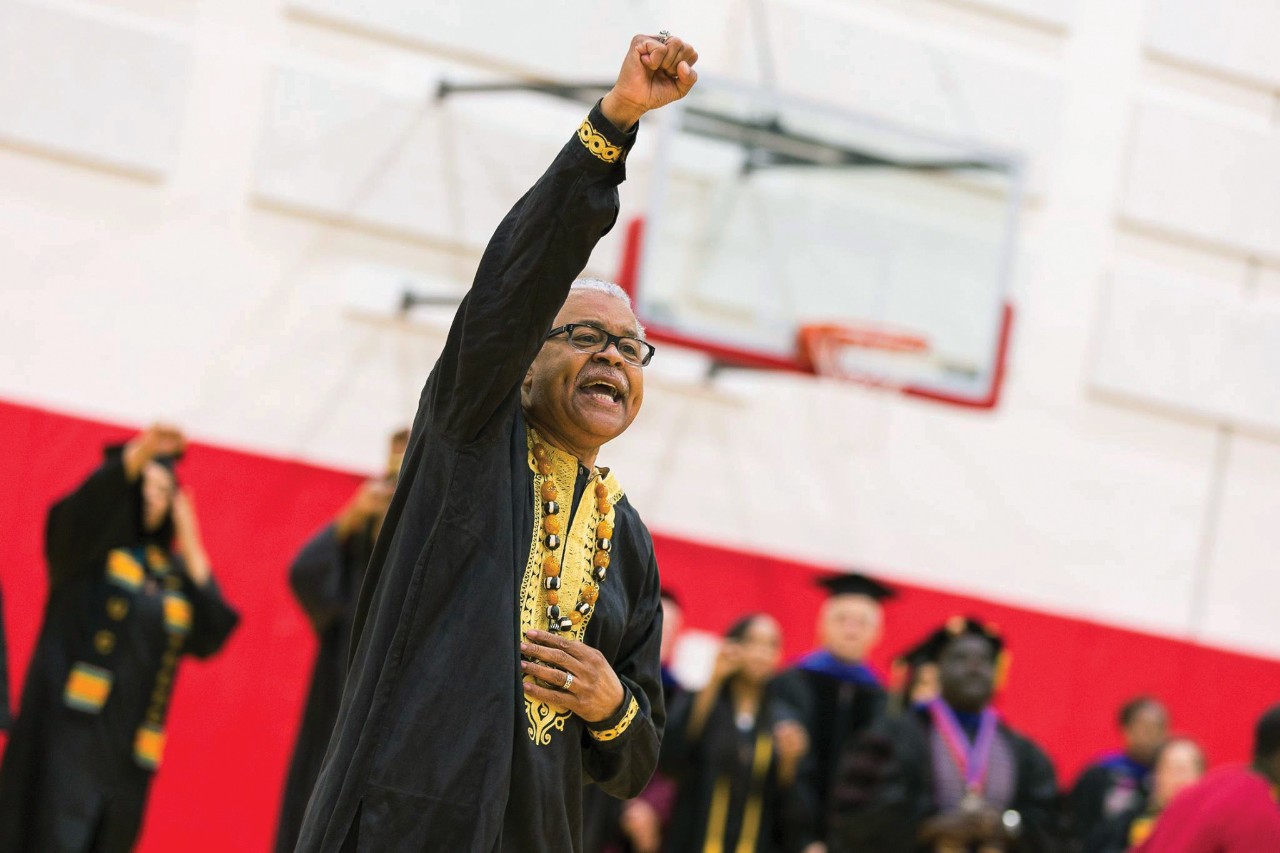

UC graduates celebrate in the Tyehimba ceremony. The Tyehimba program grew out of the African American Cultural and Resource Center's activities.

Doc through the decades

Eric Abercrumbie's UC business card from 1975.

Abercrumbie began his UC career on Sept. 1, 1972, as a counselor, first as a resident counselor in Sander Hall and then as a counselor in the Educational Development Program.

- In 1975, he was named the coordinator of Educational Programs, responsible for developing programming, workshops and seminars to supplement students’ classroom experience, with an emphasis on leadership development and communications skills as well as special interest programs and groups – such as the Black Man Think Tank and the Spring Break Tour.

- In 1987, Abercrumbie began service as the director of the Office of Ethnic Programs and Services (formerly known as the Office of Minority Programs and Services) in the Division of Student Affairs.

UC celebrates the graduation ceremony Tyehimba.

- In 1991, he was appointed as the founding director of the African American Cultural and Resource Center, and helped develop programming that continues today – including Akwaaba, the autumn welcome for incoming black students, and Tyehimba, the annual graduation celebration of student success. Akwaaba serves as an introduction to campus services and student organizations in an effort to keep students connected throughout the school year. The Tyehimba cultural celebration is an expression of thanks to family, friends and the community for their assistance and support to graduating students. The word "Tyehimba" means "we stand as a nation."

- In 2013, he assumed his long-standing role as executive director for diversity and community relations within Student Affairs, where he is now director of special projects.

- In fall 2018, he was named special assistant to UC President Neville Pinto.

Abercrumbie also served as an adjunct faculty member in the Department of Africana Studies, teaching courses such as “The Black Man in U.S. Society” and “The Adolescent Black Male.” And his love of classroom teaching motivated him to earn his doctorate in interdisciplinary studies at UC in 1987. (And it was after earning that doctorate that students began calling him “Doc.”)

And truth to tell, earning that doctorate was a personal and professional pivot point for Abercrumbie, who pursued the degree with support from faculty like Lowanne Jones, emerita in Romance Languages, and Lantham Camblin, emeritus in educational studies.

Abercrumbie states, "Many black men can go their whole lives and never be called mister. Earning the doctorate conferred some legitimacy both in the classroom and outside of it."

Whatever his title, Abercrumbie’s role has been a wholly consistent one as a mentor, counselor, agitator, educator, firebrand and father figure.

- Read a few first-person recollections from those who have known Doc over the decades.

Abercrumbie reflects, “This is where God planted me. When I came here, I was a baby. Now, I feel I’m a grandfather to our students. I was the original diversity liaison, and UC still needs strong black faculty and staff as role models and to help tackle the issues that are here and in our larger society too. A lot of my sweat is in this place. I’ve always given my best.”

UC just dedicated the new Dr. P. Eric Abercrumbie Living Learning Community at Siddall Hall to honor Abercrumbie's impressive legacy. This dedicated area will be home to 80 first-year students who have been accepted into the Darwin T. Turner Scholars Program or the Transitions Program. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

Well-earned honor

Brandi Elliott, director of UC's Office of Ethnic Programs and Services, congratulates Eric Abercrumbie at the announcement that a new living learning community would be dedicated in his name. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

The enduring nature of Abercrumbie’s legacy will be exemplified by 80 incoming students joining the UC campus in fall 2019.

These first-year students, all recipients of the Darwin T. Turner Scholars Program and/or the Transitions Program, will participate in a dynamic living-learning educational community in Siddall Hall, the newly designated P. Eric Abercrumbie Living-Learning Community.

A living-learning community (LLC) focuses on creating bonds between students, faculty and staff around specific interests both within and outside the classroom. The LLC named for Abercrumbie will foster personal and social identity development, leadership development and engagement as well as academic success.

At the announcement of this honor in fall 2018, Abercrumbie – nonplussed and surprised at the recognition – was uncharacteristically speechless for several moments. His first response was a quiet, “Well.” Then, after a significant pause, an equally quiet, “O.K.”

Former students, UC staff and faculty gathered at the fall announcement of this new LLC, with Ewaniki Moore Hawkins, director for the African American Cultural & Resource Center, speaking for many when she pointed out that, in this case, LLC should stand for “love, legacy and commitment.”

Speaking directly to Abercrumbie during the event, she stated, “Your legacy, the foundation that you laid for us, is rich. And it’s strong. And it’s not going away. It lives in us, and now, it will live in the students that come to this living-learning community. They will know your name. They will know your story. They will know your core values."

She concluded, “You have shown commitment like no other.”

Trent Pinto, director, of Resident Education & Development (RED), explains that the LLC is a partnership between RED, the African American Cultural & Resource Center, Ethnic Program & Services and Housing & Food Services, and it “cements the university’s commitment to ensuring for the years to come that students in these programs have a space to call home on campus. Through the living-learning community, the university honors the history and legacy of Doc, while providing future students the opportunity to create their own paths and leaving their own marks at UC and in the larger community.”

At the close of the recognition ceremony, Abercrumbie reflected that the honor “has brought me full circle. This is where I began. I started my UC career as a residential hall advisor to students. And now a residential hall community bears my name.”

Eric Abercrumbie gets emotional at the announcement that a living learning community at Siddall Hall would be dedicated in his name. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

Redirection not retirement

Abercrumbie insists that his official retirement date of May 1, 2019, is not the date he will retire but the date that he will instead redirect his energies.

Currently, he’s not sure where that redirection will specifically lead, but he’s looking forward to the future and the final assessment on his legacy.

And that ultimate legacy is what he’s been striving for throughout his UC ministry: “No person can be great unless they show they have contributed to other people’s lives who don’t look like them. I truly believe that. I think that’s the mark of people who make needed contributions. And if I died today, I know that not everyone who came to my funeral would look like me. That’s success.”

Material in this tribute to Eric Abercrumbie draws from a February 2018 profile by UC’s McMicken College of Arts and Sciences.

Become a Bearcat

Learn more about Campus Life and Student Affairs. Check out how to apply to UC, whether undergraduate and graduate programs.

Related Stories

From research to resume: Grad Career Week prepares students for career paths

February 20, 2026

Graduate students at the University of Cincinnati will explore how their academic and creative work translates into professional success during Grad Career Week, March 2–6, a week-long series of workshops, networking opportunities, and skill-building sessions hosted by the Graduate College.

Before the medals: The science behind training for freezing mountain air

February 19, 2026

From freezing temperatures to thin mountain air, University of Cincinnati exercise physiologist Christopher Kotarsky, PhD, explained how cold and altitude impact Olympic performance in a recent WLWT-TV/Ch. 5 news report.

Blood Cancer Healing Center realizes vision of comprehensive care

February 19, 2026

With the opening of research laboratories and the UC Osher Wellness Suite and Learning Kitchen, the University of Cincinnati Cancer Center’s Blood Cancer Healing Center has brought its full mission to life as a comprehensive blood cancer hub.