Recycling: Everybody’s doing it? Not exactly.

UC students examine views on recycling in one Cincinnati neighborhood

Recycling is a widely known way for individuals to do their part to help preserve the environment. People collect glass, plastic and paper throughout the week and then take a recycling cart to the curb for pickup. Easy, right?

Ease of recycling in Cincinnati, however, depends on where or how you live, what your views are on recycling and confusion over what can be recycled, according to a research project conducted by University of Cincinnati psychology majors.

“We looked at what influenced people to recycle, what restricted people to recycle, why it is important to recycle as well as some general trends to why or why not people recycle,” says Leo Readey, one of 13 UC students who surveyed the inner-city neighborhood of South Cumminsville and recycling habits there for a course-based senior capstone project.

South Cumminsville is one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods with a history of having a lower than average level of household recycling.

The study was a research partnership between the University of Cincinnati, Working in Neighborhoods (WIN), the city of Cincinnati’s Office of Environment and Sustainability and waste and recycling firm Rumpke and is an example of UC’s emphasis on urban impact, an element of the university’s Next Lives Here strategic direction.

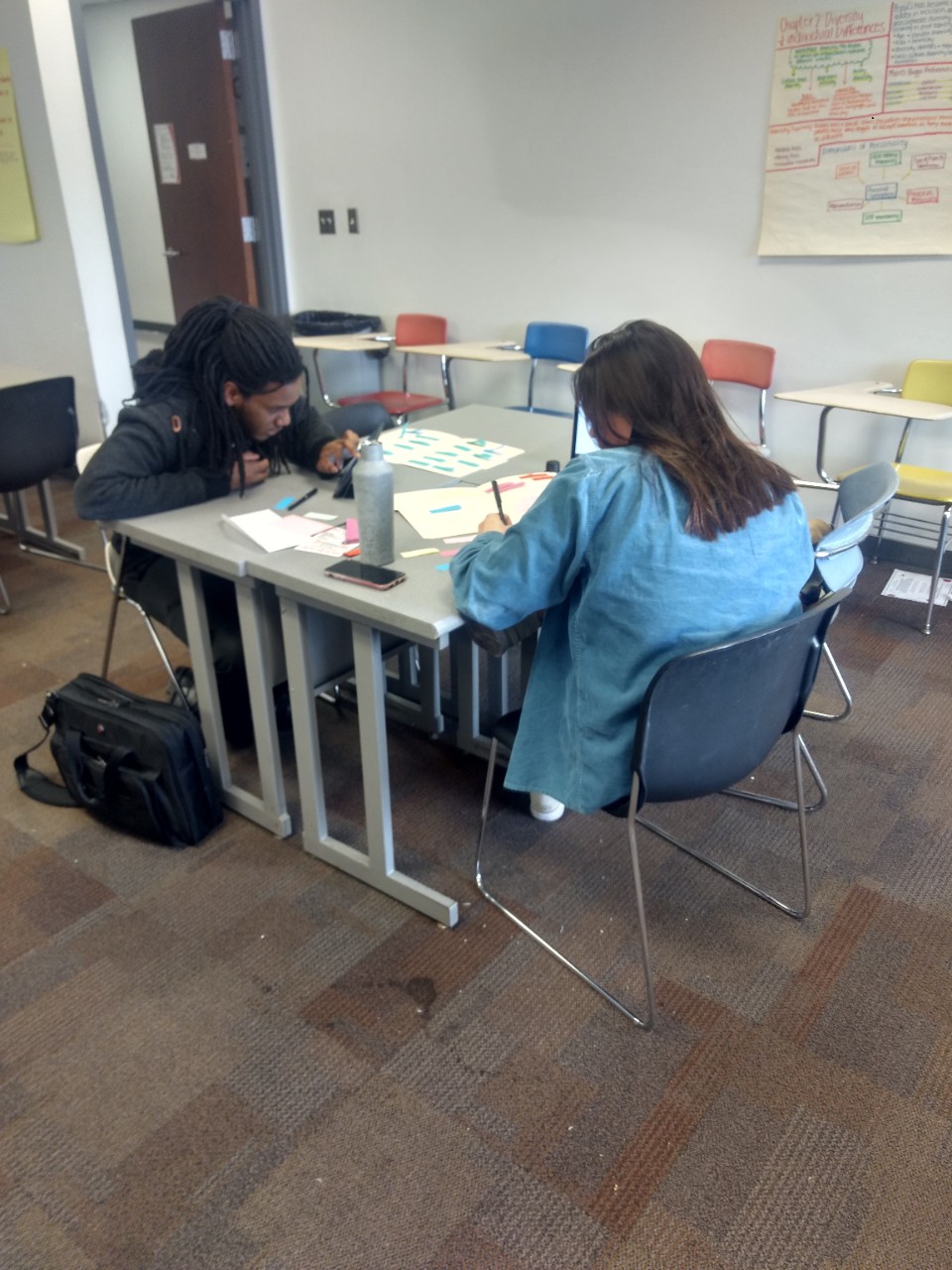

Students meeting with residents of South Cumminsville to survey their opinions on recycling and find ways to improve recycling habits in the community. Photo provided by Trott.

Over the course of 15 weeks, Readey and his student peers were trained in community-engaged research methodology such as focus group data collection and qualitative analysis. Study participants were then recruited door to door by WIN volunteers to participate in focus groups.

Participants included 28 South Cumminsville residents between the age of 21 and 77, with the average age of participants being 58.6 years. Of the 26 participants to complete a socio-demographic survey, 20 (76.9%) were female and six were male (23.1%). The majority of participants were black or African American, two were mixed race, three were white and the remaining did not indicate their race or ethnicity.

The project began in December 2018 when Sue Magness, recycling coordinator for the city of Cincinnati, contacted Carlie Trott, an assistant professor of psychology, with the idea to identify and address neighborhood-based recycling disparities in the city. Planning continued throughout the spring and summer of 2019 prior to the project’s launch in the fall semester.

Early in the semester, Magness and Rigel Behrens from WIN visited campus as guest speakers in the capstone course. Later, students met in their own small groups to collect and analyze data and interpret and write up findings, which were presented at Cincinnati’s city hall in December 2019.

“It was real action-based research, where students get to be involved in their community to make a difference,” says UC’s Trott.

After data was gathered, UC students formulated ways to improve recycling habits in the neighborhood and presented to Cincinnati officials. Photo provided by Carlie Trott.

According to the research summary findings: “There was a strong sentiment of leaving the world better for future generations and to show the youth to recycle and to keep their communities clean and well cared for. Several people mentioned that they believe recycling is a civic duty and is simply the right thing to do. Some also mentioned that it is important for the environment and wildlife.”

The study also highlighted some of the barriers to recycling, such as living in a multi-unit dwelling, where there might be little room for household recycling containers or the absence of an exterior recycling cart and confusion over what can and cannot be recycled. For example, student Readey notes, one participant pointed to a single serve plastic chip bag from a lunch meeting and questioned why it didn’t qualify as recyclable.

“In theory everything is recyclable, but it’s not economically feasible,” explains Magness who has led Cincinnati’s recycling efforts in the city for over 20 years.

According to Magness, in the plastics category, only bottles and jugs can be recycled. The “chasing arrow” with the number inside the triangle is a resin code. The chasing arrow does not mean the item is recyclable. This can be confusing, she says, because for years people have been taught to look for the chasing arrows as a universal signal that an item can be recycled. However, what items can be recycled is determined by markets, and that can vary from city to city and state to state.

“In theory everything is recyclable, but it’s not economically feasible."

Susan Magness Recycling coordinator for the city of Cincinnati

Trott, whose research focuses on engaging young people in their communities — especially toward addressing sustainability challenges, says she was impressed by the way the students honed in on the project and how their research knowledge base expanded over the course of the project. “At times I thought I was sort of tossing them into the deep end, by positioning them as the study’s primary investigators, but by midterms they were really beginning to see the value of their work.”

Readey echoes Trott’s evaluation: “This firsthand account of recycling factors helped to pinpoint areas where the city of Cincinnati could realistically make improvements in order to make a difference in household recycling… and because the study is relevant to our everyday lives. It made me think about my own recycling habits and what I could do to improve them as well as get my friends to do so as well.”

While the study provided students the opportunity to engage in real-world research, it also provided the city a low-cost opportunity to reevaluate its recycling education efforts and work toward raising recycling rates throughout the city, says Magness. “I would have never been able to afford the study if it weren’t for these students. It just wasn’t in my budget.”

Featured image at top of trash for recycling/Unsplash

Next Lives Here

The University of Cincinnati’s strategic direction defines our moment and our momentum. More nimble and more robust than a plan, Next Lives Here announces our visionto the world — to lead urban public universities into a new era of innovation, impact and inclusion. Be a part of an institution that values inclusion, and apply today.

Related Stories

Scientists discover how snakes stand upright without limbs

March 12, 2026

Earth.com highlights a study co-authored by UC Professor Bruce Jayne, an expert in snake locomotion, about how snakes stand upright without arms or legs.

Pi Day: Where math meets dessert

March 12, 2026

Pi Day is celebrated on March 14 around the world, as March 14 represents its first three numbers, 3.14. It’s a yearly celebration for math lovers to see who can recite the most digits, talk about its history and have an excuse to eat many, many pies! First, the math: PI is the Greek letter “π” and it is the symbol used in mathematics to represent a constant, as it is the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter. It has been calculated to over 50 trillion digits beyond its decimal point and will continue to repeat, as it is an irrational and transcendent number.

Engineers develop deft solution to orient robots in space

March 11, 2026

To keep a repair robot stable while fixing satellites in space, University of Cincinnati engineers took a page from experts in balance: bull riders. UC College of Engineering and Applied Science graduate student James Talavage and Professor Ou Ma looked at simple but effective ways for a robot to maintain orientation while working on a broken satellite in zero gravity.